Mercy Joins the Call at Paris Climate Talks to Keep Fossil Fuels in the Ground

Special Reports: December 15, 2015

Editor: Mercy had five representatives at COP21: Áine O'Connor rsm (Americas), Bridget Crisp rsm (Aotearoa New Zealand), Marianne Comfort (Americas Institute Justice Team) and Margaret Twomey rsm and Carmel Bracken rsm (The Congregation). On 9 December, Mercy co-sponsored two side events on the international movement to ban fracking fracking. [The flyer for the events are here.]

Image: Consequences of Fracking. iStock. Used under licence

The following reportregarding activities at COP21 has been received from Aine O'Connor rsm:

Keeping Fossil Fuels in the Ground

Keeping fossil fuels in the ground and banning fracking is not only possible, it’s already being done, according to panelists at two side events on 9 December co-sponsored by Mercy International Association. The events took place at the United Nations climate talks in Paris (30 November - 12 December) where country delegates negotiated an agreement to cap global warming and provide poor countries with the resources needed to adapt to climate change and develop renewable energy.

As an iconic example, panelists cited that now 'there isn’t a single fracked-gas well' in New York State, where activists, including Sisters of Mercy, put pressure on the governor over several years and in 2015, won a ban on fracking.

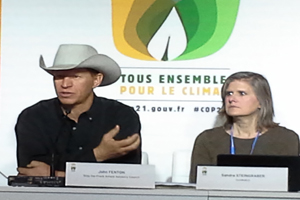

The panel included 350.org founder Bill McKibben, American biologist, acclaimed ecologist and researcher Sandra Steingraber, Argentinian trade union leader Joaquin Turco and Wenonah Hauter, author and Executive Director of Food and Water Watch. They were joined by Wyoming rancher John Fenton and Dutch Parliament member Liesbeth van Tongeren.

|

|

| L-r: Bill McKibben, Sandra Steingraber & Joquin Turco at panel discussion on: Keeping Fossil Fuels in the Ground- The International Movement to Ban Fracking |

John Fenton Wyoming Rancher & Sandra Steingraber |

Prior to the COP21 climate gathering, Food and Water Watch collected the names of more than 1,200 organizations concerned about the environmental climate, health, and social impacts of fracking, including congregations of Sisters of Mercy around the world, on a letter to world leaders urging an international ban on fracking. The panel gave voice to this call.

'We can’t bring climate change under control until we bring fracking under control', McKibben said.

Panelists disputed the notion that natural gas is a bridge between fossil fuels such as coal and clean, renewable energy such as solar and wind. Methane, which is emitted from the fracking process, has been shown to be 87 times more powerful a greenhouse gas as carbon dioxide over two decades. And there is no regulatory framework or engineering fix to eliminate those emissions since methane will always find its way through the fissures in the shale rock created by water pumped into the ground under high pressure.

To address climate change and reduce global warming, both carbon dioxide and methane emissions need to be curtailed, the panelists stressed. In fact, curbing methane emissions may be even more important, according to Cornell University scientist Robert Howarth, who was in the audience at the event. He explained that even if all carbon dioxide emissions were stopped today, CO2 would remain in the atmosphere for a very long time. Methane, however, produces more short-lived global warming and so reducing emissions would have a greater, measurable impact in the nearer term.

Panel discussion on Keeping Fossil Fuels in the Ground: The International Movement to Ban Fracking

Additionally, the panelists highlighted that water is at risk of contamination from the chemicals used in the fracking process in an industry that uses an average of 6 million+ gallons of fresh water per well and that experienced at least 6,000 spills in the United States from 2006 through 2012, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

'When you don’t have clean water in your home and clean air to breathe, you start to struggle for those daily basics', said Wyoming rancher John Fenton.

Sandra Steingraber, who turned from toxic waste researcher to anti-fracking activist when her community leased land for gas wells in 2008, listed some of the health concerns: pre-term births, children’s nosebleeds, and levels of benzene in workers’ urine at amounts that put them at elevated risk of leukemia.

Sandra and colleagues released their 3rd Edition of a Compendium of Scientific, Medical, and Media Findings Demonstrating Risks and Harms of Fracking in October 2015. The Compendium gathers and summarizes over 500 peer-reviewed studies, government reports and findings from investigative journalism. A review of the original research revealed: 84% of studies found signs of harm or potential harm, 88% of studies on air quality found elevated air pollutant emissions, and 69% of original research studies on water quality found evidence of or potential for water contamination. These results have led this group of concerned scientists and healthcare professionals to conclude that regulations to make fracking safe “are simply not capable of preventing harm.”

'Fracking is too dangerous to be regulated instead of banned,' Wenonah Hauter said.

From the perspective of panelist Joaquin Turco of the Argentine Workers’ Central Union-Autonomous, the anti-fracking cause is a union cause, as 'there is no work on a dead planet'.

A broad coalition of organizations in Argentina concerned about fracking – which has included participation by Mercy Sister Ana Siufi (74pps; PDF) and a Roman Catholic bishop -- has adopted three principles: defending territorial rights against corporations, minimizing environmental impacts and creating energy sovereignty through energy production at the community level. They are promoting an economic model that is an alternative to the dominant capitalist system that includes participative democracy and a just transition for impacted workers. So far, they can measure success in the 45 municipalities in Argentina that have declared themselves fracking free.

|

|

| Protectors at demonstration to ban fracking from climate talks |

L-r:Bridget Crisp rsm (ANZ) and Marianne Comfort (Americas) at the rally to ban fracking from the climate talks |

World Climate Leaders Don’t Frack—Protectors Give Voice Outside the Climate Negotiations

The message to ban fracking was echoed throughout the side events and in an organized and permitted rally outside the climate talks venue, where Áine O’Connor rsm and other activists talked about the social impacts of fracking, including fractured relationships between those working in the industry and those whose land has been compromised and whose health has been harmed. An Indigenous Leader from a tribe in North Dakota spoke tearfully of the impacts of thousands of men arriving in her community to work in the fracking field. Children have been sexually abused, teenagers prostituted, and some of her friends have died of heroin overdoses.

Still, she and other participants at the events found hope in the anti-fracking movement sweeping the world, from Ireland and the Netherlands to Indonesia and South Africa. They again cited the fracking ban in New York State and noted faith groups in northeastern Pennsylvania paying for water deliveries to residents of a community whose water has been contaminated. And they talked about people holding their governments accountable, country by country, state by state, municipality by municipality.

Paris Agreement Needs Just, Historic, and Do No Harm Action

Amidst the vibrant anti-fracking activism surrounding the climate talks, this past weekend, world leaders signed off on an agreement to begin addressing global warming. Hailed by many as an historic agreement, leaders have agreed to hold “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change.”

However, as the climate justice activists in Paris have made clear, to meet the 1.5 degree target by 2050, at least 80 percent of known fossil fuels must be left in the ground and fossil fuel exploration must be halted. Shale and unconventional gas extraction is not compatible with an aggressive plan needed to realistically reduce global warming enough to avert ecological catastrophe. As civil society activists stressed, a climate justice response insists that transformative steps are needed-- fracking and unconventional gas extraction must be stopped immediately. However, provisions of the agreement signed allow for countries to make only voluntary pledges to reduce their carbon emissions, and according to Bill McKibben, 'to meet that 1.5 degree target now would require breakneck action of a kind most nations aren’t really contemplating'.Thus, the work of faith based groups, social movements, concerned scientists, healthcare professionals, indigenous peoples, farmers, mothers , and young people needs to be more united than ever to compel governments to stop false, toxic, and tragic solutions for the provision of energy. Rather, there is a moral imperative to unite and push governments to act on a 100% renewable global energy strategy to be fully achieved by 2050.

Sisters of Mercy worldwide will continue to work strategically to expose the realities of fracking’s impacts on people and planet (74pps; PDF) and to realize climate justice more broadly with other social movements and with the peoples on the ground. Watch for updates and advocacy actions in 2016 on keeping fossil fuels in the ground and addressing human rights violations related to fracking, to continue to enable a mercy family response to this enormous challenge.

Messages to:

Marianne Comfort - Institute of the Americas Justice Team

Bridget Crisp rsm - Nga Whaea Atawhai o Aotearoa Sisters of Mercy New Zealand

Aine O’Connor rsm - MGA Coordinator at the UN

Avery Kelly - Fellow at MGA