![[thumbnail] Kathrine E. Bellamy rsm](../_uploads/resources/authors/164-fce1eb1c/C557E318-0BA8-E551-FF72F20FBE51DE38.jpg)

Mary Francis Creedon

A biography written by Kathrine E. Bellamy rsm

WWho was Marianne Creedon? We know very little about her. Not one word of hers was handed down to the generations that succeeded her. But we know everything that is important for us to understand, for we know what she did, and we recognize who she is for us, the Sisters of Mercy of Newfoundland — a woman who was available always for whatever God wanted, a woman who did not give up!

(1).jpg)

Marianne Creedon, the younger daughter of John and Ellen Creedon of Coolowen, County Cork, was baptized on December 5, 1811 . Nothing is known of her early childhood except that her father died in the summer of 1817 when she was not yet six years of age. Five years later, on May 12, 1822, her older sister, Ellen, married John Valentine Nugent of Waterford. A number of references have been found to support the theory that after Ellen Creedon married John Valentine Nugent she brought her ten-year old sister, Marianne, to live with her in Waterford. It is true that - to date - no record of the death of Marianne’s mother, Ellen Creedon, has been found. However, it is unlikely that a widow residing in Cork would have been able to provide her daughter with the superior educational opportunities that we know Marianne enjoyed. The Nugents, on the other hand, were all highly educated and John Valentine Nugent was an educator by profession. Growing up in such a family would account for Marianne’s well-rounded educational development.

And so the years passed. It is not unreasonable to presume that young Marianne Creedon was available to look after her sister’s children and to do her share of household chores. Church records in Waterford show that she was godmother to three of the Nugent children, an interesting sidelight on the close relationship that existed between the two sisters.

The Nugent household was not, by any means, a haven of peace and quiet. John Nugent, a devout Catholic, an ardent Irish patriot and not the most patient of men, was frequently in trouble with the English authorities. Eventually, in 1833, Nugent received an invitation from Bishop Michael Anthony Fleming of Newfoundland to move to St. John’s and establish a school for “young gentlemen”. At the time, John Nugent’s invalid mother and his sister, Maria, were living with the family. Maria Nugent had been accepted as a novice by the Ursulines but after a year’s novitiate her health broke down and she was forced to return to her brother’s home. We can only imagine Ellen Nugent’s reaction at the prospect of a lengthy ocean voyage with the responsibility of caring for two invalids and four small children. Her sister, Marianne, was now a young lady of twenty-one. No doubt she had her own friends and her own plans that may not have included a long voyage across the ocean to some unknown land. But Ellen need not have worried – young Marianne Creedon – even at twenty-one, was available to help wherever there was need of her services. She agreed to go with her sister to this New-Found-Land.

The Nugents arrived in St. John’s towards the end of May 1833. Two weeks later, John Nugent’s mother died. John, of course, had to find immediate employment to support his family. An advertisement in one of the local papers informed the public that he was opening an academy for young gentlemen and that his wife, Ellen, and his sister, Maria, were ready to receive young ladies at their school on Water Street. Miss Creedon was available to provide instruction in music. It is clear, therefore, that Marianne Creedon continued to do her share to support the family. A few months later Maria Nugent decided to join the Presentation Sisters in St. John’s, leaving Marianne as her sister’s only helper. Incidentally, Maria’s attempt to become a Presentation Sister met with the same fate as her trial with the Ursulines. At the end of her novitiate year she became ill. The Presentation Sisters, reluctant to see her leave, allowed her to make a second novitiate, at the conclusion of which she became ill once more. This time, the Sisters agreed that she should return to her brother’s home. Obviously, God had other plans for Maria Nugent.

Meanwhile, the friendship that had existed between Bishop Fleming and John Nugent since 1827 became even closer. During frequent visits to the Nugent home, the Bishop spoke of his desire to extend the benefits of Catholic education to the more affluent members of his flock and provide care for the sick poor. He had heard about a new and daringly innovative group of women who, under the leadership of Catherine McAuley, were going out from their convents to bring the message of God’s mercy into the homes of the poor and the sick. At the same time, Catherine McAuley and her followers recognized the need to educate girls at every level of society – just what was needed in St. John’s! These women were the Sisters of Mercy. Bishop Fleming knew of a group of women in Bermondsey, England, who had volunteered to go to Ireland to be trained as Sisters of Mercy, so that they would return and establish the community in England. If only he had somebody to go from Newfoundland – somebody who would make her novitiate under the direction of this Catherine McAuley, and return to establish a convent in St. John’s! And Marianne Creedon said, “Here I am. Send me.”

The Bishop was elated and lost no time in going to Dublin to see Catherine McAuley to make the arrangements. In a letter to a clerical friend Bishop Fleming outlined his plans. He proposed to send Marianne Creedon to Baggot Street to “pass her novitiate under the direction of the sainted foundress, so that she would return… and found a Convent of Mercy in St. John’s.” Fleming discovered that Catherine McAuley was quick to understand the situation in St. John’s. More than most, she understood the tensions experienced by young Catholic women in a society dominated by English Protestants. Catherine accepted his proposal to establish a Convent in St. John’s and she received Marianne Creedon into the novitiate at Baggot Street where, as Sister Mary Francis, she was professed for the diocese of St. John’s in August 1841. Bishop Fleming thought that Francis Creedon was to be the foundress of the Newfoundland mission, Catherine thought that Francis was to be the foundress, Francis thought so too, but all God wanted was that Francis be available to fulfill God’s plan.

There is a legend that Catherine McAuley wanted to come to Newfoundland herself as part of the first group of Sisters. But Catherine died and Sister M. de Pazzi Delaney succeeded – a different woman, with a different personality and different ideas. de Pazzi passed over Francis Creedon and appointed Sister M. Rose Lynch as Superior of the Convent in St. John’s. The second member of the group was Sister M. Ursula Frayne, whom de Pazzi appointed as Senior Sister. This was in keeping with Catherine McAuley’s custom of sending an experienced Sister on each new foundation to guide the fledging mission during the first months of its establishment. Francis was the junior. Was Francis upset over all this? Apparently, she was not. Francis had made her commitment – not to any plan of her own, not to Catherine’s plan, not to the Bishop’s plan, but to God’s plan.

When the three Sisters of Mercy arrived in Newfoundland on June 3, 1842, Bishop Fleming received a nasty shock. To his amazement he was informed that the person with whom he would have to deal was not Francis Creedon – who was familiar with the situation in St. John’s – but a stranger, Ursula Frayne. Ursula was an intelligent, talented, determined young woman who had very definite ideas on what the Sisters of Mercy were going to be about in St. John’s, Newfoundland. Moreover, Ursula’s ideas did not altogether coincide with the Bishop’s. Almost immediately there was tension. According to a tradition handed down by the older Sisters at Mercy Convent, Bishop Fleming by-passed the senior sister, Ursula Frayne, and consulted Francis Creedon about everything to do with the mission, which at first consisted solely of visitation of the sick and instruction of the poor in their homes. It was a very difficult situation for Francis – who was caught right in the middle of whatever disputes occurred between the hotheaded Bishop and the equally quick-tempered Ursula.

In the midst of all of this, a new problem arose. Maria Nugent presented herself to the community asking to be admitted as a Sister of Mercy. According to an undated note in the Presentation Convent Archives, Maria entered Mercy community “shortly after they [the Sisters] arrived”. Bishop Howley wrote that she entered “a few weeks” after the Sisters came; Sister M. Austin Carroll wrote that Maria entered Mercy convent “within a very short time”. Austin received her information directly from Sister M. Bernard Clune who was just one generation removed from Francis Creedon, therefore it is likely that her statement is accurate. From all of this, and in light of her profession in March 1843, it seems probable that Maria Nugent was accepted as a postulant or, possibly, as a novice by the Sisters of Mercy in August or September 1842. After spending six months with the community, the question of completion of her novitiate arose. Catherine McAuley had made her novitiate with the Presentation Sisters. Maria Nugent had already completed two novitiate periods with the Presentation Sisters, and one with the Ursulines! Bishop Fleming made his decision, “Enough is enough”, and, citing Catherine McAuley’s Presentation novitiate as a precedent, the Bishop celebrated Maria’s profession on March 25, 1843.

Ursula Frayne was outraged at what she judged to be a flagrant disregard of the Rule of the Sisters of Mercy. Once more, Francis was caught in the middle – Maria Nugent (religious name, Sister Mary Joseph) was part of the only family she knew. Francis, indeed, was in an awkward position. The situation deteriorated from that point until finally Ursula Frayne made up her mind that she had had enough of Newfoundland and its bishop. She returned to Ireland on November 18, 1843 . Rose Lynch accompanied her, but nobody knows whether or not Rose wanted to leave Newfoundland. Somebody had to accompany Ursula back to Ireland, and Rose was the logical companion. But Francis stayed — steadfast in her commitment, steadfast in her devotion to her ministry. Now there were two Sisters of Mercy left in Newfoundland, Sisters Francis Creedon and Joseph Nugent.

Meanwhile, Our Lady of Mercy School was blessed and opened formally on May 1, 1843. Until this date the Bishop supported the Sisters financially, but with the opening of the school they became completely self-supporting. After the departure of Ursula and Rose, Francis and Joseph continued the work of the school and after school hours they visited the sick. Francis was now the Superior. Days, weeks and years passed. In 1846 one of the worst fires in the history of St. John’s devastated the city. Among the casualties was the new Presentation Convent. As soon as Francis heard that the Presentation Convent was burning, she and M. Joseph hurried over Long’s Hill, the site of the fire, and brought the six Presentation Sisters back to Mercy Convent. Francis made their guests as comfortable as possible, and offered them the hospitality of the convent for as long as they needed to stay. Because it was summer time, the Presentation Sisters – who were enclosed at the time – preferred the seclusion of the Bishop’s farm some distance away, where they lived in a barn during the summer months. However, when autumn came, with cool weather and cold nights, Francis once more offered them the hospitality of Mercy Convent. On Bishop Fleming’s urging, they accepted. Francis made the whole convent available to them, keeping only a couple of rooms for herself and Joseph. Out of respect for the Presentation Rule of Enclosure, a partition was erected to separate the living quarters of the two communities. And things continued this way for another year.

Then disaster struck. In June 1847, a severe epidemic of typhus broke out in St. John’s. All the schools were closed as a preventative measure. Conditions in the St. John’s Hospital were deplorable, with crowded, inadequate facilities and unskilled nursing staff. Francis knew that help was needed urgently, and her response, as always was, “Here I am. Send me”. With Joseph Nugent by her side, she walked fearlessly into this hotbed of contagion. Every day the two Sisters of Mercy walked two miles back and forth to the hospital where they spent the day, easing the discomfort and pain of the victims, and assisting the dying. It was almost inevitable that the frail Joseph Nugent would not be strong enough to withstand the infection. She contracted the disease and for two weeks she lay dying at Mercy Convent while Francis stayed by her side trying desperately to ease her considerable suffering. On June 17, 1847 Joseph died leaving Francis alone. From the beginning she had made herself available for God’s work, for God’s plan. As she watched her only companion being buried in the place reserved for typhus victims she must have wondered, where was God now?

“This is God’s work. This is God’s problem. I will leave it to God.”Austin Carroll wrote that Francis was urged to return to Ireland. Her close friend, Sister M. Agnes O’Connor begged her to move to New York. She wrote, “You can do more work for God in New York than you can in St. John’s.” Lonely, and alone, Francis turned to God. She reflected on the words of her friend, “You can do more good in New York”. Francis did not know what good she was doing – that was God’s business. Her business was to be available, to keep the commitment she had made to God. She was professed for the Diocese of St. John’s. Even the usually confident Bishop Fleming dithered! Should Francis join the Presentation Sisters? But Francis knew where she belonged. She was committed to Mercy. She made her own decision. “This is God’s work. This is God’s problem. I will leave it to God.”

The next ten months were Francis’ Advent – her time of waiting on God. She kept the school open – albeit with a decreased enrollment. She had to support herself. She taught music, she visited the sick, and she prayed. All this time the Presentation Sisters lived on the other side of the wall, for they remained at Mercy Convent until 1851. Then, in 1948, Francis’ young niece and godchild, Agnes Nugent came knocking on the door, “I want to be a Sister of Mercy”. This presented another dilemma for Francis – who realized that the Sisters of Mercy might be perceived as a family concern. But if God was calling someone else in her family, who was she to say no? Subsequently Agnes Nugent, now Sister M. Vincent, was professed. Many years later even an anti-Catholic press acclaimed her for her deeds of goodness and charity. She was a gentle, compassionate woman who influenced the lives of many for good. Where did she learn this if not from Francis?

Now there were two. And within a short time others came. A young widow, Elizabeth Redmond entered, and then Catherine Elizabeth Bernard arrived from Limerick to become a Sister of Mercy in Newfoundland. Now there were four. Things were looking up — but not for long. In 1854 an epidemic of cholera swept through the city of St. John’s. Once more Francis Creedon responded. This time she had three others with her. Bishop Howley, who was a teenager at the time, wrote an account of the Sisters of Mercy during the cholera:

They worked among the stricken from daylight to dark and often through the night. They entered the plague-ridden houses in the filthiest slums to light fires and feed the abandoned wretches. They scrubbed floors and cleaned the tenements. They dressed and washed the sick and finally carried their dead bodies to the coffins which were placed outside the door by fearful officials who refused to enter the plague houses.

This time the Sisters were spared. But hundreds of people died and dozens of children were orphaned. Francis could not forget the plight of these poor homeless children and she saw a way to help. Bishop Fleming, who died in 1850, had left money to build an orphanage at Mercy Convent. It was time to act. Francis consulted with the new Bishop, John Mullock, and as a result, the Immaculate Conception Orphanage was opened at Mercy Convent on December 8, 1854. Meanwhile, on the same day Francis accepted first Newfoundland-born postulant. Her name was Anastasia Tarahan, the first of three sisters who were professed as Sisters of Mercy in Newfoundland. But in spite of the help offered by the new recruit, the opening of the orphanage meant additional work for all the Sisters. There was no Government help in those days. But Francis continued to do all that she was called upon to do. She made a home for homeless children, she kept the school open, she visited the sick. She was steadfast in the hope and expectation that God would fulfill God’s plan.

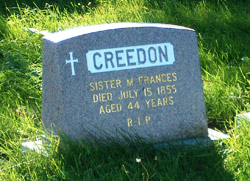

By the spring of 1855 Francis was beginning to wear out at the age of forty-three years. The reception of the postulant, Anastasia Tarahan was set for July 2, 1855, but a few days before the ceremony, Francis collapsed. Nevertheless, on the day of the ceremony she was available to receive Anastasia, now Sister M. Baptist, into the novitiate. During breakfast someone came to the door to ask for a Sister to attend a person who was dying. Francis wanted the three young Sisters to continue celebrating the reception of the new novice. So, taking Elizabeth Redmond with her, she donned her bonnet and cloak and started off down the steep hills of St. John’s on what was to be her last visitation. The next day she was unable to leave her bed. She died two weeks later on July 15, 1855. Bishop Mullock noted in his diary, “Mother Creedon died today at 2 o’clock, worn out by her efforts for the poor and sick of this town.”

The local papers carried no obituary. Francis Creedon departed this life the way she lived it – quietly, without ostentation, without any acknowledgement. She was, indeed, another “woman wrapped in silence”. But we remember her as being available to God and for others; as being someone who faced loneliness and difficulty and steadfastly refused to abandon her mission; a woman of faith and hope – who expected God’s plan to be fulfilled; a valiant woman who persevered in the face of seemingly insurmountable difficulties. Above all, we honour Francis Creedon as a woman who meant what she said when she declared, “Here I am; send me.”

When we read of other women who founded numerous convents and attracted hundreds of followers, we might be tempted to look at Francis Creedon as a failure. She was trained by Catherine McAuley to be a foundress, but someone else was appointed. Nevertheless, Francis was the foundress of the Newfoundland Congregation, but not in the manner that she had anticipated. She became the foundress because others – for whatever reason – gave up. The Sisters of Mercy are in Newfoundland today because Francis was steadfast in her commitment, because she believed that it was God’s plan that the Sisters of Mercy should be messengers of God’s love and mercy in this lonely, ruggedly beautiful little island in the north Atlantic.

The lesson of Sister M. Francis Creedon’s life might be summed up as follows:

The lesson of Sister M. Francis Creedon’s life might be summed up as follows:

To be at peace in the midst of tension, to be faithful to a commitment when everyone is urging you to give up, to wait in joyful hope and to believe that God’s plan will be fulfilled in God’s time and in the way that God chooses.

Francis’ message to us might be found in the words of an unknown author:

“We need to keep our eyes fixed on the Lord our God until God lets us rest.

And then we will know, as we have always known that the effort was worth

the gift of our lives,

the best of our years,

the length of our days.”