-

A reflection from Mary Reynolds rsm

Catherine – Model for Life and Ministry

April 30, 2014

We can look at Catherine’s life & Ministry in the following ways:

- Focus of her Life & Ministry: Passion for Christ and passion for Humanity

- Soul of her Life & Ministry: Reflective Living

- Style of her Life & Ministry: Empowering and Participative

- Heart of her Life & Ministry: Relationships

- Tools of her Life & Ministry: Communication and connection

- Difficulties in her Life & Ministry: Conflict and Loss

- Supports in her Life & Ministry: Friendship and Humour

Focus of her Life & Ministry: : Passion for Christ, Passion for Humanity

When describing the mission of the Congregation or identifying the qualities necessary for becoming a Sister of Mercy, Catherine was very clear: 'an ardent desire to be united to God and to serve the poor'. She described the Spiritual and Corporal works of Mercy as 'the business of our lives'. How she enfleshed this vision is well known to all of us - provision of education and training, visitation of the neglected in the slums, hospitals and prisons, care of the sick in their homes and in the cholera depots.

Looking at what she did through the focus of Leadership, these are the elements that I believe are noteworthy.

1. Her approach was wholistic. Her focus of passion for Christ and passion for humanity was never compromised. Catherine kept in mind that the faith element of her work was central and so her decision to join her education system to the newly established National School system was taken, only when she had established that there would be adequate freedom to conduct religious instruction in the schools.

Her care and training of vulnerable women included a basic training in their faith and in Christian morals. It was in the persuit of this that she engaged in a bitter conflict with the parish priest at Westland Row in an effort to get the services of a chaplain on a continuous basis. She nursed in the cholera depot and visited the sick in the nearby protestant hospitals, mainly to bring spiritual comfort to the dying.

2. The second characteristic was the emphasis she put on professionalism and high standards. This sprung from her profound respect for the dignity of the human person and from her belief that in ministering to poor people, she was ministering to Christ. Catherine often spoke of the privilege this was and how service of people should reflect this. Before setting up her schools, she acquainted herself with current techniques and procedures in France and in the prestigious Kildare St. school and to improve standards, she set up the first Monitress training college in Ireland. Her nursing standards in the Cholera depot were so high that the death record there was less than half of any of the other city depots. Even in the visitation of homes, she insisted with her Sisters that they would attend to the comfort and cleanliness of the sick as well as to their spiritual comfort.

3. The third characteristic was the way she used her status in society to the advantage of the poor. Catherine dressed up as a lady of fashion to present herself at Sir Patrick Dunn’s hospital and gained permission of Protestant officialdom to visit and comfort the dying – something no priest could do. She did the same in gaining access to Kildare St. school. She used herconnections with Society families to place young women trained at Baggot St. and indeed to attract donations of money and helpers for her work from among them. She used her easy entrance to the company of Church and State authorities to progress her work, counting the Archbishop of Dublin and the renowned politician Danial O’Connell among her loyal supporters in the service of her mission.

Soul of her Life & Ministry: Reflective Living

We are familiar with the unending demands that were made on Catherine and her followers in the service of the poor. They could easily have become immersed in responding to these many needs to the exclusion of all else, yet as Catherine would remind herself and the Sisters: 'What advantage are our works to God? But our working hearts He longs for, and he pleads for them with touching earnestness'.

Yet, Catherine did not wish her Sisters to become contemplative in the accepted sense of her day. Indeed she worked tirelessly to avoid that. When she was away at George’s Hill, some of her young enthusiastic followers, wanted in their fervour to imitate what they had seen contemplatives do like night vigils, long hours of prayer, etc. But Catherine went so far as to charge her Carmelite priest friend to keep an eye on Baggot St. and to ensure that the young women did not engage in these practices. When Claire Agnew tried to move in the direction of enclosure and Perpetual Adoration, Catherine clearly laid out a document, insisting that this was not the spirit of the Mercy Congregation. Catherine promoted the idea of ‘contemplation in action’ which was a new concept for the traditionally cloistered religious. She had learned how to utilise the activities of each hour as the matter of her reflection and she never accepted a dichotomy between contemplation and ministry. Rather, she insisted that active works must be done without losing awareness of the presence of God, and she was convinced that the Sister of Mercy must make mission the ambience of her recollection.

In expanding on that conviction in her Retreat Instructions she said: 'Prayer, retirement and recollection are not sufficient .We should be like angels who while fulfilling the office of guardians, lose not for a moment the presence of God or as a compass that goes round its circle without stirring from its centre. Our centre is God from whom all our actions should spring as from their source and no exterior action should separate us from Him. The functions of Martha should be done for Him as the duties of Mary'.

Catherine had a way of reminding her Sisters that the works of Mercy are not theirs but God’s. It was this belief that gave her the freedom of spirit to move forward with works and move back from them as circumstances dictated. The poor always remained God’s poor and though she was called to serve them, their care was basically God’s affair. As a result she had a heart centered in God.

Catherine was one of the first to promote a vision of apostolic spirituality. Just as Christ considered as done to himself whatever was done to others, she was convinced that all Sisters of Mercy should be a sign of Christ’s presence among his people. In this regard, she urged them to be like a lamp kindled with the fire of divine love, shining and giving light to all and she told them: 'If the love of God really reigns in your heart, it will quickly show itself in the exterior. You will become sweet and attractive in manner. You will have a tender esteem for everyone, beholding in them the image of God'.

In a very real sense Catherine’s ‘apostolic spirituality’ was part of her search for personal union with God and it was marked by her ability to create and maintain inner spiritual space, to be constantly aware of the mystery of God and to be everywhere in the world of people. 'The streets will be our cloister,' she said. She herself embraced the importance of a profound inner life which would enliven and support a generous service of the poor, and this very service would itself be a powerful means of union with God. 'No occupation,' she said, 'should withdraw our minds from God. Our whole life should be a continual act of praise and prayer.'

The salient characteristic of Catherine’s vision and entire life was an expression of love of God through service of people. Her realism led her to try and alleviate human need of every kind; her idealism convinced her that the Spiritual and Corporal Works of Mercy are a means of closer union with God, and she compared the Sister of Mercy who does not actively serve God’s people to a knife that grows rusty or a well that becomes stagnant from want of use. To neglect either prayer or apostolic service for the sake of the other would be to deviate from her founding intention.

Two practices which Catherine encouraged as a support to apostolic spirituality were ‘the sacrament of the present moment’ – the notion that ‘what is now’ is where God is for me, and the practice of silence 'The practice of the presence of God is one-half of holiness,' she said. 'We belong to God, all in us is his. We must endeavour to keep ourselves in his presence, united with him by faith.'

Speaking of Silence she said 'Spiritual advancement generally takes place in the hours of silence. In silence God will work on our interior life if we allow him. Recollection, leads to familiarity with God – uniting us with him as one friend with another.'

In describing this characteristic of Catherine, Angela Bolster rsm said: 'In all the travel and turmoil of her life Catherine was at home within herself with the indwelling Lord. She radiated the tranquillity of inner intimacy; while the unseen realities to which her faith gave her that access allowed her to treat lightly and good humouredly the surface happenings that could have daunted another… She showed how every experience and event can be shot through with grace and be shaped so as to shine bright with the gladness of Redemption'.

Some would say that Catherine’s greatest contribution to the Church is not the congregation itself as much as the spirituality that enlivened it – a fresh and fertile blending of the contemplative spirit and the compassionate heart. It is a spirituality that alerts us to how God is with us in all the most ordinary activities and moments of our lives.

To achieve a proper balance or rhythm between contemplation and action, to have the disposition of Mary to receive and ponder the Word of God and to act upon it, is a crucial challenge for us today, just as it was for Catherine and her first companions.

Teilhard de Chardin, echoes Catherine’s vision. He saw Christianity as the illumination of the existing world, forging bonds between inner faith and faithful work: 'By virtue of the Creation and, still more, of the Incarnation, nothing here below is profane for those who know how to see. On the contrary everything is sacred. Try, with God’s help to perceive the connection – even physical and natural – which binds your labour with the building of the kingdom of heaven… For what is sanctity in a creature if not to adhere to God with the maximum of one’s strength? And what does the maximum adherence to God mean if not fulfilment – in a world organised around Christ'.

The challenge for us, as it was for Catherine, could be summarised in the beautiful words of the Irish poet, Paul Murray OP: 'I am that still centre within you, that needle’s eye through which all the threads of the universe are drawn'.

Style of her Life & Ministry: Empowering and Participative

Catherine believed in authority and leadership that was life-giving and liberating. As we know, she shunned any monastic trappings of office. She wished to avoid the special title Reverend Mother and she never used the title in her correspondence with the Sisters; and she would not allow the Sisters to stand when she entered or left the community room. When she visited the Sisters in Carlow, they were deeply impressed by her humble manner and the annalist notes: 'the most amiable trait in her character which we believed we discerned was a total absence of everything in her manner telling, I am the Foundress'.

She maintained a loose hold on the reins of authority. She entrusted full authority to very young Sisters, but she was there to support and encourage.. She allowed the young superiors to use initiative, stepping back to do this, but knowing when she should intervene in the most appropriate and tactful manner possible. Her style was adapted to suit the person she was dealing with; she could encourage the initiative of the resourceful Frances Warde, spur on cautious Elizabeth Moore in Limerick as evidenced in several warm letters or when writing to Mary Ann Doyle, be firm and direct. 'Do not fear offending any one. Speak as your mind directs and always act with more courage.' When Catherine felt the need to admonish, she did it tactfully and often softened it by using playful verses. When Sister Ursula Frayne was superior in Booterstown, she wrote to Catherine for permission to buy a new pair of boots and also complained that the cups supplied by Baggot Street were too small. Catherine teased her about her spirit of poverty.

With great trust in her Sisters, Catherine readily applied the principles of collegiality and subsidiarity long before these became the widely used terms that they are now. She freely sought advice of all in the community, shared information with them and involved them in decision making. The Dublin manuscript records: 'At the first Recreation the business of the convent was talked of as freely as if it were a Chapter of Discreets'. The whole community was involved in the decision to make the Presentation Rule the one which would be the basis of the Original Mercy Rule. The Derry manuscript says simply: 'They all chose the Presentation Rule'. As always, Catherine was not adverse to fun even in the midst of weighty decision making. For example, when the appointment of a superior for Birmingham was under discussion, one English postulant offered her services and Catherine wrote as follows to Frances Warde:

'They [the English Sisters] are most interesting, two so playful that they afford amusement to all at recreation. One about 20 – not looking so much – thinks she will be best suited for superioress at Birmingham, makes up most amusing reasons'.

On another occasion, when a bishop from overseas had come to Baggot Street to request Sisters for his diocese, Catherine prompted the newest postulant to stand up and offer to make the foundation! The bishop got the message – he would have to wait a little longer for his wishes to be fulfilled.

In more serious circumstances, Catherine willingly shared with her much younger Sisters, treating them as peers and respecting their wisdom. Many believe that the rapid development of the congregation was due in no small measure to the way in which she formed superiors after her own heart. Even at the end, she refused to name a successor. When a Sister spoke to her of this and asked her to show her preference, her only response was to insist that the Constitutions gave the Sisters freedom to choose.

Heart of her Life & Ministry: Relationships

It is interesting that Catherine did not write or speak in a theoretical way about community, defining or analysing it in terms as we might today. She wished simply to be one of the sisters, shunning the formalities which generally marked religious life in her time. She wanted love, not regulations, to bind the Sisters together. Her true affection and love made her wonderfully free and natural with the Sisters. She encouraged cheerfulness, delighted in fun and liveliness. At recreation, she would laugh and sing, she would compose playful verses to amuse and to instruct in a light-hearted way. The contemporaries of Catherine invariably recalled her great approachability and naturalness, her liveliness and cheerfulness, her kindness and solicitude for each Sister, her unpretentious way of being in their midst.

Her love was manifest in concern for all the Sisters in every aspect of their lives. It made her miss them in their absence, grieve with them in their sorrows, rejoice with them in their successes, forgive them in their weaknesses and gently urge them to greater courage in their following of Jesus on the way of Mercy.

From the outset, Catherine wanted a family spirit to reign in the community. Mary Clare Moore gives us an insight on this:

'Being of a remarkably cheerful disposition, she loved to see all under her charge happy and joyful. She tried to make them so, not only by removing whatever could disturb their peace, but also by contributing to the general cheerfulness of the Community especially at Recreation. Although burdened with many cares, she was at that duty as lively and merry as the youngest Sisters, who used to delight in being near her, listening to her amusing remarks and anecdotes. She had a natural talent for composing verses in a playful style, and would often sing them to some cheerful tune with admirable simplicity. She was a great enemy to that spirit of sadness and discontent which destroys true devotion, nor could she suffer them to take a gloomy view of passing events'.

We know that Catherine delighted in fun and liveliness. She recommended that there be a piano in every community room and across the top of one of her letters she wrote in big letters 'Dance every evening'.

Catherine had an immense freedom of spirit and she rejoiced to find this in others so that Mercy communities would be marked by a love which respected others in their difference and uniqueness. Writing to Elizabeth Moore at Easter, 1841, when there were busy preparations being made at Baggot Street for receptions and professions involving English novices and at least one lay sister, Catherine gives us a glimpse of her ideal of Mercy community:

'All are good and happy. The blessing of unity still dwells amongst us – and oh what a blessing – it should make all things else pass into nothing. All laugh and play together, not one cold, stiff soul appears. From the day they enter, all reserve of an ungracious kind leaves them. This is the Spirit of the order indeed – the true Spirit of Mercy – flowing on us… Take what He will from us – He still leaves His holy peace – and this He has graciously extended to all our Convents'.

The true spirit of Mercy was God’s gift, creating a strength of unity founded on love. Catherine was not suggesting that the Sisters were free from the weaknesses of human nature, but she believed that the ordinary happenings of community life, and the ordinary tensions and weaknesses among the Sisters, were opportunities for developing compassion and tolerance and for practising forgiveness and reconciling love. It was in this strain that she wrote to Elizabeth Moore in Limerick in 1839: 'One thing is remarkable – that no breach of charity ever occurred amongst us. The sun never, I believe, went down on our anger. This is our only boast – otherwise we have been deficient enough – and far, very far, from cooperating generously with God in our regard, but we will try to do better'.

What Catherine most rejoiced in was the spirit of forgiveness and reconciliation which enabled the Sisters to live in union and love. Jealousy and gloomy depression in a sister concerned Catherine, as we know from a letter she wrote to Frances Warde. It related to Teresa Carton, whom Catherine had brought to Booterstown to improve her health. It seems Teresa was dependent on Catherine’s affection and that she feared the others might take over her work at Baggot Street. Catherine writes:

'I hurried out here to get poor Teresa into change of air. She is already evidently better, but is fretting so much for being taken from her employment that I fear the good effect will be lost. She has given me much uneasiness by the gloomy peevish manner she behaves every day since she came. The collection goes on just the same with Sister Aloysius… She distressed me very much yesterday – I almost thought she was sorry to hear the collection children went on as usual – perhaps I was mistaken. Please God she will triumph over this human weakness – and I rejoice at the good which must result from her seeing that those things do not depend on any one in particular, but on the continuance of God’s blessing'.

Catherine encouraged a selfless attitude in her Sisters and it is variously recorded that she often conveyed such wisdom as: 'Our love for others ought to be so cordial, that we should never refuse to do or to suffer anything for the good of our Sisters'. In another place she expands on the word ‘cordial’: 'now "cordial" signifies something that revives, invigorates, and warms; such should be the effects of our love on each other'.

A good summary of how important Catherine felt relationships were is found in her poetic advice to the young and fretful Elizabeth Moore who had been appointed Superior to Limerick – a city in which 3 Congregations had failed in making foundations:

Patience and approachability: 'Don’t let crosses vex and tease, try to meet all with peace and ease. Be mild and sweet in all your ways ; Keep patience ever at your side; you’ll need it for a constant. Show fond affection every day

Challenge with love: and encourage : Notice the faults of every day – but often in a playful way. And when you seriously complain, let it be known to give you pain.. Avoid all solemn declaration, all serious close investigation. Turn what you can into a jest, and with few words dismiss the rest. now and again bestow some praise.

Manage time: Attend to one thing at a time; you’ve fifteen hours from 6 to 9. Pray : Above all fondly pray ,that God may give the charge He’s given and make of you their guide to Heaven'.

While Catherine certainly lived among her Sisters, treating them as friends and valued companions, it is consoling to know that at times she was exasperated by some of them. She once remarked: 'To live with a saint in heaven above, oh! What eternal glory. But to live with a saint on earth below is quite a different story'.

Among those who challenged Catherine’s patience was the temperamental, artistic Clare Augustine Moore. Catherine found her exasperating at times – her slowness and perfectionism sometimes irritated her as on one occasion when she requested her to print two pages and Clare Augustine could not oblige. Catherine complained to Frances Warde:

'Sister Mary Clare [Augustine] Moore is a character – not suited to my taste or my ability to govern – though possessing many very estimable points. She teased and perplexed me so much about the difficulty of copying the two pages, that I was really obliged to give up – unwilling to command lest it should produce disedifying consequences. She said it would take the entire Lent – indeed you can have no idea how little she does in a week – as to a day’s work, it is laughable to look at it. She will shew me 3 leaves, saying I finished these to day – 3 rose or lilly [sic] leaves'.

Similarly, Sister de Pazzi Delany tried Catherine’s patience. She was Catherine’s assistant in Baggot Street after Mary Anne Doyle went to Tullamore and Frances Warde to Carlow. Lacking confidence and prone to attacks of epilepsy, de Pazzi tried to control Catherine’s absences from Baggot Street. She often showed displeasure at her prolonged stays in the foundations and would greet her return with a long tale of woe. She was constantly bemoaning the transfer of Sisters from Baggot Street in order to staff new foundations. Catherine’s only remedy was to ‘outmoan’ de Pazzi, as she explained in a letter to Sister de Sales White in Bermondsey:

'Mother Mary de Pa[zzi] and I have kept up the most musical sighing or groaning in the Bishop’s parlour. I thought she was far surpassing me – and yesterday I determined not to be outdone and commenced such a moaning as brought all to an end'.

Another insight regarding relationships that Catherine had was the influence of courtesy upon community harmony. The Bermondsey annals record:

'While she passed over without seeming to notice them many inadvertant [sic] offences, she was most watchful to correct in their [the Sisters] conversation or manners the least failure against politeness, and anything which could discover the want of a good education, being convinced by experience that the inattention of some Religious persons to these minor points often lessens charity in a Community'.

Catherine's hope for the shared life of her Sisters was that each person would be treated with love, respect and dignity

During her last days, Catherine had several affectionate messages for each Sister in the community and for the foundations she had made. Though constantly in great pain and weakness she would say after a sleepless night: 'I was thinking of my poor children in Birr during the night'. In her dying hours her thoughts went in compassion to this last foundation in Ireland, with its special need for support, and she commended it to the Sisters around her bed: 'Take care of my last born – Birr'.

Early on her last morning Catherine asked for all the Sisters to be brought to her and to them, and through them to us, she gave her last precious words: 'My legacy to the Institute is charity: If you preserve the peace and union which have never yet been violated among us, you will feel, even in this world, a happiness that will surprise you and be to you a foretaste of the bliss prepared for every one of you in heaven.'

As her last moments drew near, Catherine whispered to the Sister assisting her: 'Be sure you have a comfortable cup of tea for them [the sisters] when I am gone – the community room would be a good place'.

Tools of her Life & Ministry: Communication and connection

If there was one thing that distinguished Catherine is was her ability to make connections. In her ministry she connected the rich to the poor, the healthy to the sick, the educated and killed to the uninstructed, the influential to those of no consequence, the powerful to the weak to do the work of God on earth. She was able to communicate hope in a society where poverty and destitution were widespread and to offer an alternative vision. She was able to animate many at the centres of wealth, power and influence to share her vision and become passionate about the possibility of change.

Catherine had just two tools at her disposal for communication and connection – her letters and her personal visits. As we know her letter writing was phenomenal and we have already noted some of the personal visits she made in the service of her mission. We will look in more detail at her letters to the Sisters but from the letters that survive, the list of recipients give us a glimpse into so many facets of her Leadership.

She wrote to Bishops and clergy about new foundations and about the affairs of new foundations. She wrote to architects about designs and buildings, even at times giving very precise directions on room dimensions, furniture, etc. She wrote to benefactors and potential donors asking for or thanking for support. She wrote to potential employers about positions for young women in the house of Mercy. She wrote to Government officials about the service of the Sisters in the Cholera Depot and to others about registration of the schools. She wrote to her legal advisers about threatened court proceedings and about financial affairs. She wrote to Medics about Sisters’ illness..It is amazing to consider her volume of correspondence at a time when all letters were handwritten and there was absolutely no secretarial support.

Her travels were just as amazing. Catherine utilized all modes of transport as she embarked on her travels. Post chaise, railway car, canal barge, packet and steamer carried her to Tullamore, Charleville, Carlow, Limerick, Galway and Birr within Ireland and to Bermondsey and Birmingham in England. She was negotiating foundation journeys to Liverpool and Newfoundland during the weakness of her last illness. When one considers that a trip to Cork would take 3 days and a trip to Limerick or Galway between a day and 2 days, we cannot but admire her stamina in being able to endure the cold, discomfort and sheer exhaustion of such journeys.

Most of all Catherine wrote to and visited the Sisters. When her Sisters were suffering any loss from sickness or death she would make great efforts to visit them and when this was not possible she would write to them. In one such letter she wrote to Frances Warde:

'I have been uneasy about you since I heard how you have been affected, though I am aware there may not be any serious cause, for Sister Mary Teresa White had the same kind of attack – yet I know you are not sufficiently cautious… Now let me entreat you not to be going through the new Convent, or out in the garden, even on the mildest day during this month – without careful wrapping up'.

When there was danger of an over-serious spirit ruling in a community, she would write and urge a little nonsense and play, as we see in one of the Tullamore letters. It seems that the Tullamore superior, Mary Anne Doyle, was traditional in some of her ideas about the austerities of religious life as we can glean from a comment by Catherine. 'Mother M. Anne has met with her ‘beau-ideal’ of a conventual building at last, for our rooms are so small that two cats could scarcely dance in them. The rest of us however would have no objection to larger ones.'

On leaving Tullamore, Catherine was somewhat uneasy about Mary Anne’s seriousness and rigidity of government, so much so that she wrote a month later to the new postulant Mary Delamere planning some fun for her next visit. Her intention was to relax Mary Anne and to assure Mary Delamere of the great joy inherent in the religious state. The letter is entitled “A Preparatory Meditation” (written a month before the reception ceremony).

'My dear Sister Mary, It has given me great pleasure to find you are so happy, and I really long for the time we are to meet again – please God – but the good Mother Superior will not have equal reason to rejoice, for I am determined not to behave well, and you must join me. If I write to mention the day we propose going, you might contrive to put the clock out of order – though that would be almost a pity. By some means we must have till ten o’clock every night not a moment’s silence – until we are asleep – not to be disturbed until we awake. Take care to have the key of the cross door, and when those who are not so happily disposed go into Choir, we can lock them in until after breakfast. I fear Sister Mary Clare [one of Catherine’s travelling companions] will join the ‘Divine Mother’ – she is getting rather too good for my taste. Sister Catherine is according to our own heart, and surely Sister Eliza [another postulant] will not desert us.'

She then makes reference to Mary Teresa, the novice who came on the Tullamore foundation and who became assistant to Mary Anne Doyle on the day Teresa was professed.

'My dear Sister Mary Teresa describes a melancholy night she passed while her mother was so ill. We must banish all these visionary matters with laughing notes hop-step for the ceremony, to be concluded with ‘The Lady of flesh and bone’. We will set up for a week what is called a nonsensical Club. I will be president, you vice-president, and Catherine can give lectures as professor of folly.'

Catherine’s care of the Sisters in the foundations was phenomenal. She encouraged them to gather for ceremonies of receptions and professions and to visit one another in the new convents. The Bishop of Galway commented: 'It is impossible the order of Srs. of Mercy should fail – where there is such unity and such affectionate interest is maintained, as brings them one hundred miles to encourage and aid one another, and this is their established practice, to look after what has newly commenced'.

Catherine constantly kept in touch with all the leaders of the foundations, calling her letters her 'Foundation Circulars' to the 'Foreign Powers'. There were constant references in her letters to the individual Sisters in the communities – their needs, their health, their families, the friends of the local community, the parish clergy and the local activities. To one superior she wrote: 'Give me a true and faithful account of your charge – to each of whom give my most affectionate love'. And to another, her words were: 'How I long to hear of you and dear community… You will write a long account to me – a letter that I may shew [sic] to all'.

All too often Catherine was sharing the sad news of the sickness and death of sisters and her letters often convey the depth of her own personal pain and loss on those occasions. On hearing of the death of a young sister in Limerick, one with whom she used to exchange verses, she wrote:

'I did not think any event in this world could make me feel so much. I have cried heartily – and implored God to comfort you – I know He will… My heart is sore – not on my account – nor for the sweet innocent spirit that has returned to her Heavenly Father’s Bosom – but for you. You may be sure I will go see you – if it were much more out of the way – and indeed I will greatly feel the loss that will be visible on entering the convent'.

Sometimes her letters conveyed news that was very topical, as in January, 1839, when a violent storm ravaged Ireland – talked about for years as “The Night of the Big Wind” – she wrote a graphic and vivid account to put her anxious sisters in touch with the aftermath:

'The accounts from Limerick were as usual exaggerated but we heard the Convent was safe… We remained in Bed all night – some in terror, others sleeping… The Community Room a complete ruin in appearance… the Prints and pictures all on the ground – only two broken. The maps and blinds flying like the sales [sic] of a ship… 16 panes broken… The windows are still boarded up – it is almost impossible to get a glazier – a fine harvest for them… The Sisters in Carlow passed the night in the choir – part of their very old roof blown down. The chimneys of the new Convent in Tullamore blown down – the old one & Sisters safe'.

The 200+ extant letters of Catherine are another insight into her leadership. The woman writing to keep all foundations abreast of one another is affectionate, tender, tender, funny, graceful, confiding, wise.

The woman of business is direct, concise, well-bred.

The woman writing to Bishops and priests is open, candid, cordial, respectful and dignified.

The woman who is Superior writing to censure is pained. She sandwiches reproof between affectionate greeting and long newscast to insure that the sister remains assured of her affection.

What shines through Catherine's letters as she encourages, cajoles, persuades, praises, finds fault, consoles or spurs onwards is that whatever God permits is blessing.If accepted, every cross will be turned into joy, into power to do good. There is no passivity in what she says. Her letters to her Sisters are in effect her way of effectively inspiring, animating and unifying the newly founded congregation.

Difficulties in her Life & Ministry: Conflict and Loss

Catherine’s decision to invest her inheritance in the service of the poor led her into much conflict. Some of her relations were disappointed and felt cheated of an inheritance they hoped would fall to them in the event of her not marrying. They dubbed her house ‘Kitty’s Folly’. A number of the residents of the fashionable homes in Merrion and Fitzwilliam Squares were none too pleased either. They complained that the house was a plain, unadorned building and that her venture focussed on the “thankless poor” and was downgrading the locality. Their hostility was shown when Catherine decided to appeal to the Catholics of the neighbourhood for subscriptions for the upkeep of the House of Mercy.

The venom of some of the replies is recorded by Clare Augustine Moore 'N… knows nothing of such a person as C. McAuley and considers that C. McAuley has taken a very great liberty in addressing her. She requests that C. McAuley will not trouble her with any more of C. Mcauley’s etc. etc.'.

A more offensive letter came her way in 1829 from a priest that addressed her as C. McAuley ESQ and berated her on the impropriety of a woman encroaching on such masculine prerogatives as business, finance, philanthropy and religious foundations. Clerical criticism was something to which Catherine was particularly sensitive.

One of Catherine’s greatest critics was Canon Matthew Kelly of Saint Andrew’s Parish, the parish in which Baggot Street was situated. He and other clerics claimed that she and her companions were looking and acting conventual and trespassing on the apostolic field of Mary Aikenhead’s Irish Sisters of Charity. At one point he indicated to her that the Archbishop wished her to give the house over to the Sisters of Charity.

Catherine was particularly devastated by these criticisms. She had carefully schooled herself to handle opposition with compassionate understanding, but opposition from those whose interests she supposed to be the same as her own left her not knowing where to turn. So deeply hurt was she by those attacks that on the day the chapel in Baggot Street was blessed and opened as a public oratory, she could not bring herself to attend the opening Mass but stayed alone upstairs. One of her early biographers captures the emotion of the day: 'She was much affected on that day and would not be present at the ceremonies but remained in prayer in the convent. At this time and long after, she had much to feel from disapprobation expressed by many priests and others'.

While the Archbishop supported her, he was also cautious. He was pleased with the work but not entirely happy about the fact that she and her companions who were not a religious community, were beginning to look remarkably like one. Eventually, this of course led to the founding of the Mercy Congregation. Even then, Catherine had to endure many misunderstandings. The term ‘walking nuns’ was at first used derisively by those who failed or refused to understand this new form of religious life.So much speculation existed on their Church status and degree of respectability that Catherine urged he Archbishop to approve a written approval from Rome on their efforts. Approval was granted on March 24, 1835

Two conflictual situations caused Catherine extreme anxiety: one was the so called chaplaincy dispute; the other was the Kingston controversy. The chaplaincy dispute again involved Doctor Meyler. He insisted on abandoning a long-standing arrangement whereby Baggot Street had one special chaplain who was to serve the sisters, the women and the children of the house. Catherine regarded the provision of a special chaplain as essential for the personal direction and consistent spiritual care of all. Doctor Meyler wanted his three curates to serve on a rotational basis. He also insisted on a payment of £50 per annum but all Catherine could offer was £40. The tone of some of his correspondence to her on the matter was unaccommodating and, at times, sarcastic and hurtful. The personal cost to Catherine of this dispute can be glimpsed in her correspondence with the Chancellor of the Diocese, Reverend John Hamilton, which she finishes with the words: 'The only apology I can offer for writing is that it comforts and relieves my mind to declare the truth, where I trust I am not suspected of insincerity'. In one of her letters to Frances Warde, she wrote: 'We have just now indeed more than an ordinary portion of the Cross in this one particular'. Elsewhere in the letter we get a glimpse of the pain, the hurt and the struggle as she writes: 'Pray fervently to God to take all bitterness from me. I can scarcely think of what has been done to me without resentment. May God forgive me and make me humble before he calls me into his presence'.

At the same time that Catherine was so distressed by the chaplaincy dispute, she was engaged in troublesome financial and legal problems over the Kingstown convent which, as she said, constituted a 'real portion of the cross' for her. In 1835, she opened a convent in Sussex Place, Kingstown as a rest house for convalescent sisters. Soon the plight of the poor, especially that of young girls who roamed the street, challenged her to further involvement. The parish priest, Father Sheridan, who was described by a writer of the day as “a shrewd financier”, welcomed Catherine’s proposals for transforming some unused stables and the coach house in Sussex Place into a school, but he made no financial commitments and Catherine walked into a commitment that she had not anticipated. Her letter to her lawyer puts the case plainly:

'Mr [Father] Sheridan seemed quite disposed to promote it [the project for a school] and brought Mr Nugent [Builder] of Kingstown to speak about the plan. When that was fixed on, I most distinctly said in the presence of Mr [Father] Sheridan that we had no means to give towards the expense, but to encourage a beginning, I promised to give all the little valuable things we had for a bazaar that year, and to hand over whatever it produced'.

She accordingly gave the builder £50 pounds, and in so doing incurred liability for the entire debt which amounted to something in the region of £400.

Several months of legal wrangling followed. The only way that seemed open was to sell or lease Sussex Place and, with eviction facing the Sisters, they had to withdraw from Kingstown. Catherine herself was branded a “cheat and a liar” by Mr Nolan but this caused her less grief than the pain caused to her and the sisters in having to abandon the poor of Kingstown. An insight into that pain is evident in the letter that she wrote to Sister Teresa White, the Superior of Kingstown:

'Be a good soldier in the hour of trial. Do not be afflicted for your poor. Their Heavenly Father will provide for them and you will have the same opportunities of fulfilling your obligations during your life. I charge you my dear child, not to be sorrowful, but rather to rejoice if we are to suffer this humiliating trial God will not be angry. Be assured of that and is not that enough?... He will not be displeased with me, for He knows I would rather be cold and hungry than the poor in Kingstown or elsewhere should be deprived of any consolation in our power to afford. But in the present case, we have done all that belonged to us to do, and even more than the circumstances justified'.

Loss and bereavement of family members, close friends and supporters and Sisters of the Community were a constant in Catherine’s life. Just as she was starting the Baggot St. project her sister Mary died in 1827. The following year her trusted adviser Fr.Armstrong died and in 1929, her brother in law William Macauley died and she became legal guardian to her 2 nieces and 3 nephews

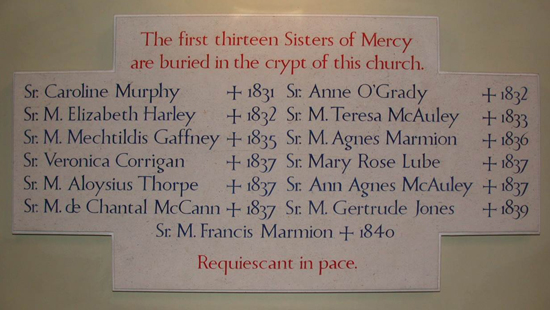

Catherine’s greatest source of anxiety was the sickness and premature deaths of so many young companions. Even before she returned to Baggot Street from George’s Hill, death had claimed the life of 19-year old postulant, Caroline Murphy, and another postulant, Anne O’Grady, was seriously ill. The reception ceremony of the first seven novices on January 3, 1832, just three weeks after the foundation of the congregation on December 12, should have been a very joyful occasion. But the joy was shadowed by the fact that as the ceremony took place in the chapel, Anne O’Grady was terminally ill upstairs. On February 8, she died and was buried alongside Caroline Murphy in the vaults of St Teresa’s Church, Clarendon Street.

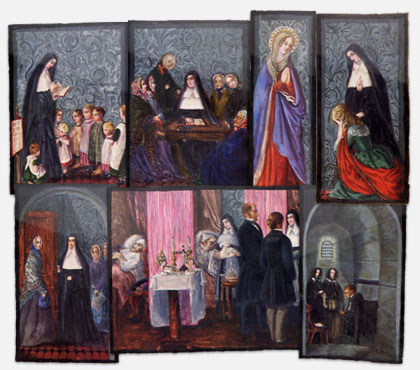

Plaque on the wall in St Teresa's Church, Dublin above the Mercy crypt

In March, the outbreak of Asiatic cholera struck Dublin and on April 25, little more than four months after her profession in George’s Hill, Sister Elizabeth Harley died. Catherine had great hopes that she would be her principal support in those founding days but the regime at George’s Hill, where she worked in a damp basement, had taken its toll on her health and in her weakened state she succumbed to the cholera epidemic. No wonder that Catherine would remark: 'The Congregation was founded on Calvary, there to serve a crucified Redeemer'.

Tuberculosis, cholera and typhus, as well as exhaustion from overwork and frugal nourishment caused a high level of sickness. Indeed, it was in order to provide a place for recuperation and restful breaks that the convent in the seaside location of Kingstown (today Dun Laoghaire) was opened. Unfortunately, as we know, this did not work out as intended. Catherine, in the course of the ten years of her life as Mother Superior to her new band, accompanied the funeral cortege of ten more of her young sisters to Clarendon Street. In 1837 alone, five young sisters died. Ellen Corrigan, an orphan who had lived with Catherine since she was a child, died on 9 February, having made her profession on 25 January. A week later, Mary Rose Lube professed her vows on her death bed and died on 11 March. On 30 June Aloysius Thorpe died of typhus. Just imagine the pain that Catherine must have carried in her heart as she presided over four professions and two receptions the following day, and then, four days later started out on a foundation to Cork.

But her anxiety was even more greatly increased when she was called back to her seriously ill niece and god child Catherine Macauley who was in the advanced stages of consumption. It was a tiring journey and on 27 July she wrote: 'I am weary of all my travelling and this morning I fell down the second flight of stairs'. Young Catherine died on 7 August and her aunt’s mixture of sadness and relief are captured thus: 'Our innocent little Catherine is out of this miserable world. We feel now as if all the house was dead. All are sad to part with our animated sweet companion… Thank God it is over' . On October 27, the fifth sister that year, Sister de Chantal McCann, died two weeks after Catherine’s great support and friend, Doctor Nolan, Bishop of Carlow. Earlier that year in April, he had welcomed the new foundation to Carlow.

While this extreme experience of loss was being sustained, the ‘chaplaincy controversy’ and the ‘Kingston controversy’ were raging. Does it surprise us that in November, as she struggled to cope with it all, she fell down the stairs again, this time in Kingstown, and broke her left wrist?

In the following years, as well as five other deaths in Baggot Street, there was the death of Kate Coffey, a postulant in Carlow who had developed a brain haemorrhage after a fall on ice; another postulant in Galway, who died suddenly on the day she was to be received, while the foundation was still in process; a novice in Limerick, Mary Teresa Potter, for whom Catherine had particular affection and with whom she had exchanged several witty poems, and two novices in Bermondsey who had contacted typhus after visiting a family where the parents and seven children were dying of the fever. No wonder she would say: 'The tomb seems never closed in my regard' or 'my heart is sore', but she adds: 'In grief, let us unite ourselves with that Heart, which was sorrowful even unto death'.

Willie, often referred to as ‘wild Willie’ , the youngest of her adopted children, went to sea in December of 1838 at the age of 17. Unfortunately he parted on bad terms with Catherine. He did not come to see her at all before his departure because of his anger with her for referring to him as a “spoiled child” in one of her letters to her brother (who was the one responsible for sending him to sea). He also resented her efforts to challenge his wild ways. Catherine never again saw or communicated with Willie and although he later spoke and wrote of his Aunt Catherine with great affection, she went to her grave unreconciled with him and pained by his loss in her life.

Her 2 nephews and adopted children also pre deceased her, Robert in 1840 and James in 1841.

Catherine’s prayer: 'Take from my heart all painful anxiety' sprang from a heart that was often heavily burdened, but when life presented her with its inevitable losses, struggles, conflicts and disappointments, she embraced the cross with faith and with an understanding that she was being called to share the suffering of Christ. She knew well the limitations and vulnerabilities that suffering uncovers in human beings but she maintained a wisdom that accepted the cross. Based on her own experience she could proclaim 'without the Cross, the real crown cannot come'. In this way Catherine transformed conflict and loss.

Supports in her Life & Ministry: Friendship and Humour

All of life involves some kind of loneliness. There is a loneliness that comes from criticism or failure, a loneliness of seeing something that others do not see, a loneliness of carrying too much of the burden alone. Catheriene experienced such loneliness and sometimes needed the refuge of a trusted friend. For her, this was Frances Warde. Catherine once said of friendship: 'It will be a source of great happiness – for which I thank God – a pure heartfelt friendship which renews the powers of mind and body'.She considered life to be inconceivable and intolerable without friends. She believed in friendship as the Spirit’s way of illuminating our lives, of affirming and consoling us and of reassuring us of the future to which we all are destined.

Frances was an immensely energetic, strong and vivacious character and there was a mutuality between these two women of great courage and great dreams. From the beginning, she was able to support Catherine in the practical administration of the community and it was to her that she entrusted the care of financial affairs at Baggot Street when she was away at George’s Hill.

Over time, Frances became Catherine’s closest confidante, yet when a foundress was needed for Carlow, Catherine was prepared to let her go, since she had resolved never to ‘reserve’ any sister to Baggot Street when the needs of the Church called for an apostolic work on behalf of the poor. The depth of sadness caused by this separation is tangible. And perhaps Frances had it in mind when she wrote of their final separation: 'I often think of the heaven to which [death] will give entrance, but to me it would be heaven in itself to see dearest Reverend Mother once more'. As Catherine left Carlow after the conclusion of her customary 30 days spent in a foundation, the young, fearful Frances turned to Catherine saying: 'What shall I do if we are misunderstood or persecuted or have troubles I cannot endure?' Catherine lovingly comforted her with the words: 'I will come to you, my darling'.

Yet, Catherine’s friendship was an empowering one and there were times when she judged it more advantageous that Frances needed to be encouraged to grow in maturity and independence and to come to know her own strength in dealing with difficulties. She was sadly bereaved by the death of Bishop Edward Nolan who was her great support and spiritual director, yet Catherine left an interval of time before visiting her. In her letter, which she wrote from Cork to her, Catherine struck this lovely balance between affection and empowerment:

'I will return by Carlow to see you, if only for a few hours… May God bless and animate you with his own divine Spirit, that you may prove it is Jesus Christ you love & serve with your whole heart'.

Catherine even wrote a poem entitled “Friendship”, addressed to Frances Warde in 1837, in which she expressed her thoughts on the value of spiritually-based friendship:

'Though absent, dear Sister

'Though absent, dear Sister

I love you the same

That title so tender

Remembrance doth claim

Your name oft is spoken

When kneeling alone

I sue for high graces

At God’s Mercy throne

Then I say not Religion

To friendship is foe

When the root is made healthy

The plant best doth blow

O grieve not we’re parted

Since life soon is flown

Let us think of securing

The next for our own.

This day of our mourning

Will quickly be passed

While the day of rejoicing

For ever shall last'.

Each of us carries our own anxieties as we live daily with the frustrations of our plans and hopes, with losses of all kinds, with hurt and misunderstanding even, at times, from those we love. We can feel helpless and overwhelmed, as we are confronted with the sufferings of those whose lives we touch. In the present climate of religious life marked by diminishment, loss of status, and wounded by scandals, our spirits can be crushed. The challenge for us, as it was for Catherine, is to allow our anxieties and sufferings to be a means of becoming conformed to Christ, and in coming to know our own need for the compassionate love of Christ to become wounded healers.

Messages to: Mary Reynolds rsm - Executive Director MIA