September 24, 2018

Mercy Day

Refugees and asylum seekers are hot-button issues in Australian politics and media today. The present prime minister has spoken in terms of an “invasion” of Australia's sovereignty by those coming (particularly in boats) to our country without a visa, but with valid claims to asylum under the UN Refugee Convention.1

For the past three years, I have spent a total of 5 months as a pastoral care worker for Jesuit Refugee Service at the Curtin Detention Centre for asylum seekers in remote northern Western Australia. I have also visited or volunteered in detention centres in Darwin, Port Augusta, Sydney and Melbourne. In the community, I connect with many refugees and asylum seekers who often struggle with multiple issues such as mental health, jobseeking and connections with family in their home countries. In the course of my work I use poetry to help digest the situations I encounter. I also use poems to provide a voice in English for the stories I hear, to humanise the people from the boats.

Following is a sample of creative work from myself and some of the asylum seekers I have known.

One day in a detention centre it was pouring with heavy drops of rain and someone suggested they were God's tears. I sat with a Hazara and an Iranian man, the rain bucketing around us. Having been in detention for 2 years, they related their troubles and the implications for their loved ones back at home.

It's hard to forget the shots

and what's still ringing in your ears.

It's hard to remove the pain

and years

of heavy falling rain,

becoming ever less-than-sane,

falling down amidst God's tears.

It's ripping of the heart-strings,

it's surgery of war,

it brings you to your darkest hour,

where love appears no more.

It ekes the life out from you

and every passing shower

opens the scar

as if on cue.

For love that's deepest drowns the most

and a host of other passions

blur in watercolour,

as certainties are duller

and every drop

you wish would stop

and you'd put the clouds on rations.

Yet their tears are also lonely

and if only they'd receive

a welcome from a heart that knows of loss,

no drop would ever leave

without a gift.

Though the rain may lift

and the sky may clear, across

the pain, the fear,

the flowers grow from every tear

and above, for love, a rainbow.

The same Hazara man had very good English and read out loud some poems he had written while in detention. He said that it helped to keep his mind sane and improve his language. He gave me a copy of this one and permission to share it with others. It is an honour.

This life takes so many tests

No one knows when you will stop breathing

someone shattered with sorrows

someone helpless to this situation

someone goes away leaving everything

someone is far away even when they are close

Their desire to meet

but the time is for separation

This moment of sadness

it's a very difficult moment

What is love?

This love takes so many tests

This life takes so many tests

No one knows when you will stop breathing

Somewhere a love is lost

some desire for their beloved's presence

some beautiful dreams shattered

somewhere there is a promise of acceptance

someone smile on their face

someone tears in their eyes

What is this agony?

This desire of heart takes so many tests

No ones knows when you will stop breathing.

One day I was talking to another Hazara man from Afghanistan who had been on the run from the Taliban for 10 years, in Iran and Pakistan. He could never settle or get a steady job. He said he was like a thief, always on the watch for police. Never fitting in, he did not feel like a human. Only now, in the detention centre, was he starting to feel human again.

I live like a thief in the night.

I hide away,

keep out of sight.

I quake with fear

at a flashing light,

but, even so, it's worth the flight.

Have you stared down the barrel of a gun?

Are you kept many days

from the sun?

Do you leave

when your work's just begun?

Do you know what life's like on the run?

And I run from place to place.

Always hiding,

not showing my face.

I leave life

without a trace.

Am I part of the human race?

Another day I met a Hazara man who had just received his refugee status.

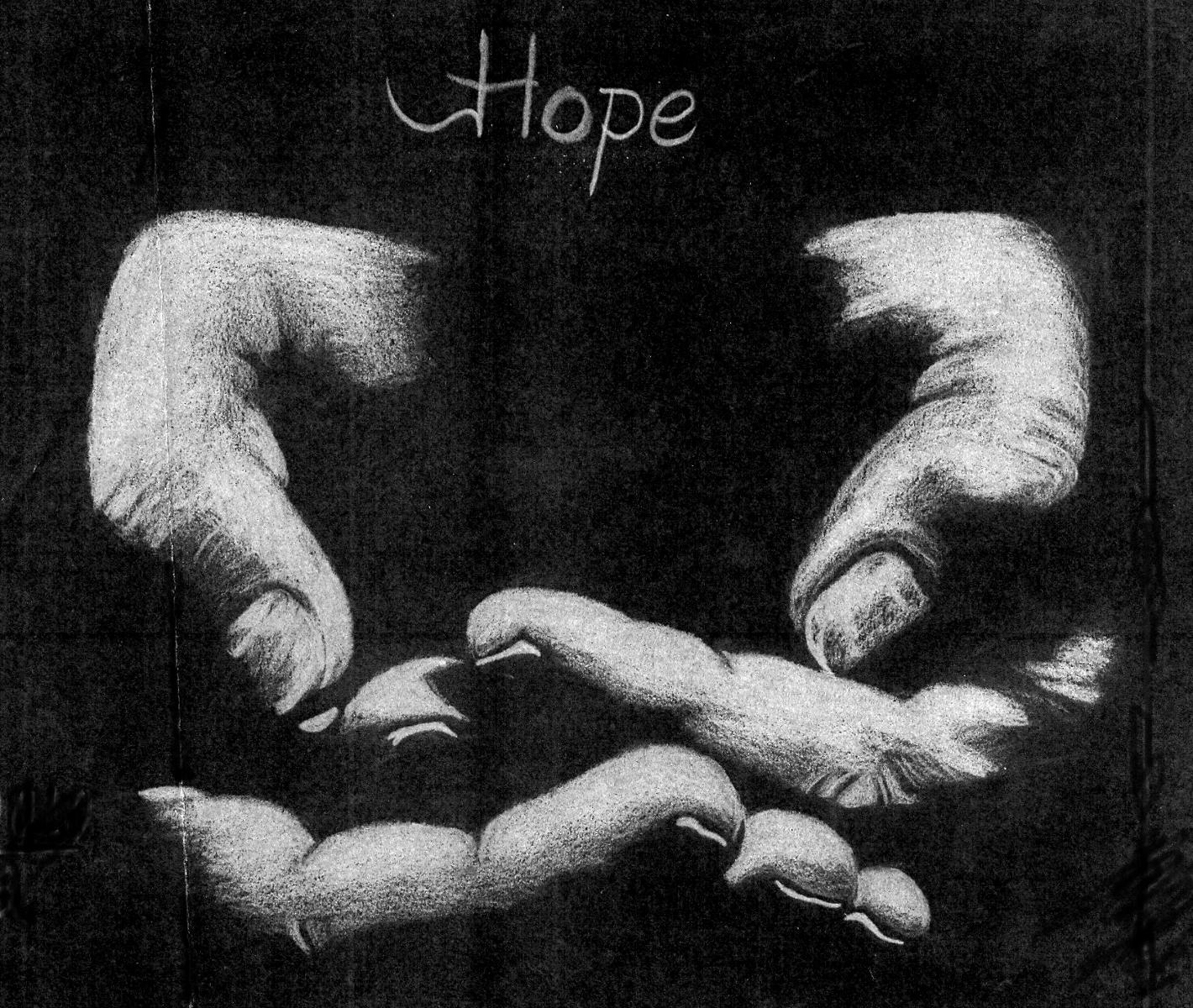

His friends doused him with water to celebrate – soon he would leave with a visa. The man was a memorable character: small and lively, with a high-pitched voice. He had been a teacher in a girl's school in Pakistan and he showed me photos of his students and himself playing the bagpipes. However, it wasn't living in detention that he discovered his artistic talent. He had drawings throughout his room and the common dining areas: his daughter; a mother, raising her child above her head in the sunset; a man crouched, dejected by a wall; a soldier saying goodbye to his family; a man hiding his face; a husband and wife; Joseph and Mary on a donkey. The artwork said it better than words. He was the one person who said that he would miss the detention centre. There he had gained health and weight, had his teeth fixed and become an artist. The most moving of his drawings was in a separate booklet he was compiling for his wife, on black paper with white chalk. Some weeks later, the day before he left, he gave me a copy and permission to share it with others. He said, “You should never give up hope!”

Messages to: Elizabeth Young rsm

1. Spike in arrivals is peaceful invasion

For more information about asylum seekers and refugees in Australia: