September 24, 2018

Mercy Day

It is easy for us to think of Catherine as the heiress who inherited so much through the generosity of Mr. Callaghan and who spent her vast inheritance with abandon for the sake of those who had little or nothing. Maintaining and sustaining what she had initiated was very challenging for her at times.

|

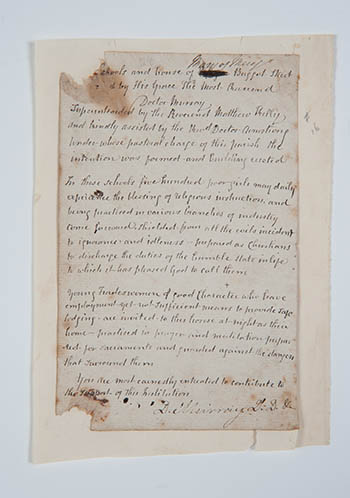

| original copy of the Door-to-Door appeal Catherine wrote in December 1827. © 2012 MIA. Photo: David Knight |

The House of Mercy opened on September 24th 1827. A few short months later Catherine found it necessary to send out an appeal for funds to those in the locality who could give financial assistance to her project. This petition, while written by Catherine herself, was signed by the Archbishop and was distributed door-to-door in the wealthy neighbourhood of Baggot Street.

The warmth of Catherine’s heart and personality comes through even in this business-like appeal. She speaks of the girls to whom she was offering safe shelter as being “invited to this house at night as their home.”

In the early years of the life of the Sisters of Mercy the two main sources of income were Charity Sermons and Bazaars. The Charity Sermon was an annual event, was advertised in the local newspapers and a cleric of some standing was invited to speak.

The following is the ad that was placed in the Morning Register on January 27th and 28th 1837:

“The Annual Charity Sermon in aid of this Institution will be preached on Sunday, the 29th instant, at half-past two o’clock, in the Church of St. Andrew, Westland-row by the Right Rev. Doctor Blake.

The Sisters of Mercy, in the name of the afflicted poor most respectfully and most earnestly beg your attendance on this occasion. Many very deserving persons await the result in painful anxiety. Should they remain longer without assistance, their appearance must become so reduced as to render their chance of obtaining a situation nearly hopeless.

The Sisters beg leave to add that it would be impossible for them to give a just description of the affliction and sufferings of the Sick Poor, who are now so numerous that they are frequently obliged to give only a few pence, where there is neither nourishment, fire, nor covering.”

Once again we meet the warm, caring Catherine. She is so concerned for the plight of the poor whose only recourse is whatever little she and her companions can offer them. She advocates on their behalf, and feels deeply the pain of their sickness and destitution. She also is painfully aware of how meagre their resources are in the face of such extreme need.

In January 1838 Catherine is beginning to fret that Fr. Maher from Carlow has not responded to the request to give the Charity Sermon in aid of Baggot Street and she writes to Frances Warde:

“He [Fr. Maher] promised to do something about the charity sermon – we have only one month. Will you coax him with all the earnestness you can. You know the contributions won’t last very long in a flourishing way. This is the season of particular pity, and if these means stop, we must stop. Oh how you should bless God who has made provision for the poor about you, not depending on daily exertions.”

Imagine the depth of Catherine’s pain when she feared that the resources needed to continue what she had started would not be forthcoming. Having to worry about money on a daily basis – these “daily exertions” – must have been something of a burden for her and may well have been one of the issues around which she prayed: “Take from my heart all painful anxiety.”

The Bazaars were generally held around Easter and by all accounts were an occasion not to be missed by the elite of Dublin. A list of the patrons of this annual event reveals that there was a definite pecking order in the social status of the day, starting with royalty and moving down through the ranks to the person of no specific social standing. The women whose names are included as patrons have the titles of Her Royal Highness, Countess, Dowager Countess, Viscountess, Baroness, Lady, Dowager Lady, Honourable Mrs., Mrs., Mrs. Colonel, Mrs. Major, Mrs. Captain.

The following is what appeared in the Morning Register on April 22nd 1835:

“To-day, the Bazaar in aid of the funds of the House of Mercy, Baggot-street, opens at the Rotundo. The attendance at this Mart of Charity is always of the most distinguished kind. Their royal Highnesses the Duchess of Kent and the Princess Victoria have not only patronised the bazaar for this most excellent Institution, but are known to have supplied some articles for exhibition and sale thereat, the work of their own hands. Our fellow-citizens of all persuasions, also have assisted in rendering it productive by attending it on each occasion, in preference to all other fashionable attractions of the day.”

The Bazaar in aid of the House of Mercy was considered to be an event where the “Who’s Who” of Dublin chose to be “in preference to all other fashionable attractions of the day!” On one such occasion in 1836 “their Excellencies” were unable to attend the first day because of being “slightly indisposed.” They were expected to attend on the second day and the announcement of that event concludes with:

“On this day we are confident that the Bazaar will be crowded with all the rank and fashion of the city of Dublin.” Morning Register, 1836, April 7.

It says something about our beloved Catherine that she was able to enlist the help and financial assistance of the wealthy to bring relief and consolation to those who were poor. No doubt her years of observing her gracious mother and her years of living with the Callaghans in Coolock House equipped her to relate with people of high-ranking social classes. As with everything else in her life, Catherine graciously put that resource at the service of those who were most in need.

Messages to: Áine Barrins rsm - Resource Person – Heritage and Spirituality

Thumbnail Image: The Irish five pund note, in circulation from 1994 -2002 depicts Catherine McAuley standing in front of the Mater Misericordiae Hospital.The reverse side of the £5 pound bill features three school children in a classroom.