September 24, 2018

Mercy Day

Click here to view Oremus Article... (pdf)

(written by - Philomena Bowers rsm)

Everything seemed to be happening at once in London on November 11th. Crowds gathered to watch the Lord Mayor’s Show; others came for the Remembrance ceremonies. Just this once, we were oblivious of the life of the nation going on around us. Even the troop of Life Guards and the noisy Flypast seemed to be put on for us. For this was our day. All morning, Sisters of Mercy, their friends, families, Associates, benefactors and co-workers, streamed towards Westminster to meet in celebration of 175 years of Mercy.

There were Mercies everywhere, snatching comfortable cups of tea at the Army and Navy; queuing ‘for time and eternity’ for the loo; old friends spotted on railway platforms; school blazers with familiar looking badges; purposeful-looking clergy clutching little cases. Some of us forgot our resolve to get there early as we dallied and chatted until the wind chill factor got the better of us. By afternoon there were blue noses as well as blue veils.

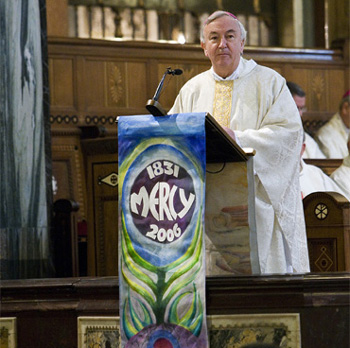

Out of the cold and into the Cathedral, all were enveloped in candle-glow and singing. Inside the great doors hung magnificent banners with Anne Hewitt’s ‘Celebrating Mercy’ design.

We marvelled that anyone with half a dozen pastels could convey Mercy so evocatively. I tried to imagine the commissioning ‘phone call: “Anne, we need you to do us a sketch of time and eternity. We’d like it to have the Holy Spirit, a Mercy Cross, Catherine McAuley and companions, generations of Mercy Sisters, and the poor and needy throughout the ages… Oh, and it needs to fit onto the front of an A5 booklet…” Barbara Jeffreys’ beautifully produced Time Line was another keepsake to treasure. Like everything else that graced the occasion, a lot of hard work went into it.

Even an hour before Mass started, finding a seat took a bit of doing. But somehow our party managed to keep together in the back row where the reassuring figure of Fr Alan could just be seen above the heads of an enormous congregation. The music he led was resounding and uplifting. Once the anxiety of finding a place had subsided, it was possible to take in the surroundings. In the seat beside me slumped a gentleman of the road, motionless, head down, grimy hands clasped in prayer. He didn’t even look up when the organ thundered out for the entrance hymn as a seemingly endless line of priests and bishops, not to mention two cardinals and the Apostolic Nuncio, processed to the High Altar. Between the vested figures making their solemn way past Basil Hume’s tomb, I caught a glimpse of Sr. Angela Robson sitting on the cold marble step, having given up her seat to an elderly Associate. This was Mercy.

I glanced down at my friend beside me: grime amidst grandeur. That was how it had been for Catherine McAuley. I hoped he might exchange the sign of peace with me, but he merely raised an elbow in gesture. I squeezed his arm. Until the offertory procession he made no movement at all. Then slowly he raised his index finger to study it intently. Perhaps the sight of Florence Nightingale had made him suspect he was suffering from concussion and he was checking how many fingers he could see. The costumes, thanks to Sr.Teresa Thompson’s nimble fingers, certainly looked authentic. There was Catherine McAuley in her black habit, a Postulant at her side. The pageant was a poignant reminder of Mercy’s influence in shaping history.

But it was Sr. Vincent Finnerty cradling the globe that kept my attention. I watched her carry it up to the Altar. It seemed as if she was representing, not the Missions, so much as our infirm and elderly Sisters who could not be with us for this great occasion but whose work of Mercy is the most frontline work of all: to bear the world to God in prayer. Their absence reminded us, perhaps, that the work of Mercy is not quantifiable. The influence of 175 years cannot be measured by how many were there or in pounds and pence, in vocations or numbers of priests on the Sanctuary. It is more like Anne Hewitt’s design, a powerful suggestion of what could be, a light that draws us towards a hopeful future.

‘Christ be our light!’ was, aptly enough, our recessional hymn. At this, the man beside me rose to his feet and slowly lifted opened hands above his head in a dramatic climax of rapt attention. What light could he so clearly see that we could not? Like Mercy’s role in God’s plan, we will never know.

Penny Roker rsm