September 24, 2018

Mercy Day

A reflective exploration of Mercy using the Gospel story of the Good Samaritan, the words of Catherine McAuley, and artwork of Clare Augustine Moore

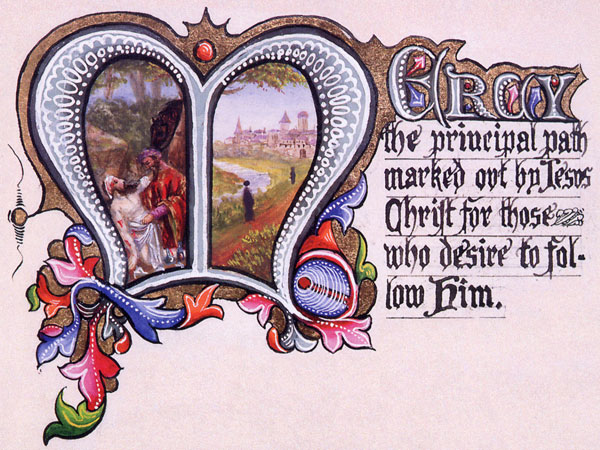

Image: Clare Augustine Moore’s depiction of the Good Samaritan story in Rule and Constitutions of the Religious Sisters of Mercy, Chapter III Of the Visitation of the Sick (PDF). Photo David Knight © MIA.

Those of us affiliated in one way or another with Catherine McAuley and her contemporaries are fortunate to have a number of extant primary sources, which convey across the centuries the genuine voice and the vision of those early inhabitants of 64A Lower Baggot Street Dublin. Amongst these is the correspondence of Catherine herself, which although not written to explicate her understanding of Mercy, does provide incomparable insight into her values and motivations. We also have her unique and defining stamp on the Original Rule and Constitutions, particularly the two sections she is thought to have composed. In pictorial form we have the 1840 series of sketches of the Spiritual and Corporal Works of Mercy by Sr. Clare Agnew. When we think of visual art and Catherine’s early companions though, our minds are most likely to turn to the exquisite work of Sr. Clare Augustine Moore that graces the early registers and other documents.

My reflection will focus on a single decorated capital letter in which Clare Augustine Moore’s art meets and accommodates Catherine McAuley’s words in the context of the Gospel. This makes it a powerful locus of the Spirit. It has further significance since it is also one of the rare instances, perhaps the only instance, where Clare Augustine Moore paints a Gospel story other than a Marian episode or the Crucifixion. So, let us explore Mercy through the Gospel story of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:30-37) as depicted by Clare Augustine Moore in its context of words penned by Catherine herself, and see how the interplay between the three elements – the Gospel story, Catherine’s words, and Clare Augustine Moore’s art- might enhance and guide our own understanding of Mercy. The material comes from Clare Augustine Moore’s illuminated version of Chapter 3: Of the Visitation of the Sick, part of the original Rule and Constitutions of the Religious Sisters of Mercy.

The Words of Catherine

While most parts of the document known as the original Rule and Constitutions of the Religious Sisters of Mercy were composed around 1835, and were painstakingly adapted by Catherine from the existing Presentation Rule, Catherine is thought to have composed from scratch Chapters 3 & 4 in late 1832 or early 1833. They both deal with ministries that were outside the scope of the Presentation Rule, but that were intrinsic to the identity of the newly formed Sisters of Mercy- visitation of the sick and dying, and care of destitute women. Mary Sullivan rsm remarks 'Chapter 3 is apparently, entirely Catherine’s own composition'.We are here very close to Catherine’s vision and voice.

In her book Catherine McAuley and the Tradition of Mercy, Mary Sullivan outlines the document’s various stages of revision and amendment, which culminated in approval of the Rule by Rome in 1841. Clare Augustine Moore’s specially illuminated copy, not to be confused with the simple 'fair copies' made by her blood sister Mary Clare (Georgiana) Moore, was produced somewhat later.

Messages to: Mary Wickham rsm