September 24, 2018

Mercy Day

Travelling Through the Dark

Travelling through the dark I found a deer

dead on the edge of the Wilson River road,

It is usually best to roll them into the canyon,

that road is narrow: to swerve might make more dead.

By glow of the tail-light I stumbled back of the car

and stood by the heap, a doe, a recent killing;

she had stiffened already, almost cold.

I dragged her off; she was large in the belly.

My fingers touching her side brought me the reason

her side was warm; her fawn lay there waiting,

alive, still, never to be born.

The car aimed ahead its lowered parking lights;

under the hood purred the steady engine.

I stood in the glare of the warm exhaust turning red;

around our group I could hear the wilderness listen.

I thought hard for us all - my only swerving –

then pushed her over the edge into the river.

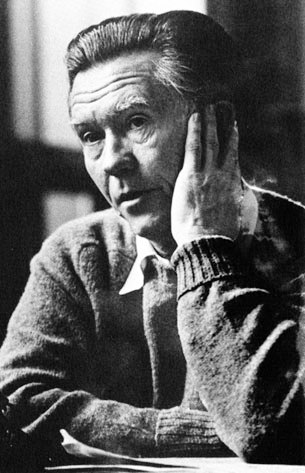

A prayer of communion can utter itself in us in various ways. This is what happen in this lovely poem by William Stafford (1914-1993). Stafford, an American poet and pacifist, went public late in life with the poetry he had always been writing. He was a college English lecturer for a number of years. His first publication, 1962, takes its title from this popular and much anthologised piece. His style is low key and conversational, but subtle in its statement. He generally gives body to his poems by telling a story of a happening in his life. Travelling Though Dark tells of an experience of travelling along the Wilson River road at night. The dark, the experience of driving, the naming of the mountain road - all contribute a sense of something that really happened.

A prayer of communion can utter itself in us in various ways. This is what happen in this lovely poem by William Stafford (1914-1993). Stafford, an American poet and pacifist, went public late in life with the poetry he had always been writing. He was a college English lecturer for a number of years. His first publication, 1962, takes its title from this popular and much anthologised piece. His style is low key and conversational, but subtle in its statement. He generally gives body to his poems by telling a story of a happening in his life. Travelling Though Dark tells of an experience of travelling along the Wilson River road at night. The dark, the experience of driving, the naming of the mountain road - all contribute a sense of something that really happened.

The first verse is quite perfunctory. We get a sense that this happening is quite common for motorists on this wilderness road, and that the dead animal had to be removed if more serious accidents were to be avoided, due to the swerving of cars.

But there was more happening for Stafford than just a journey from A to B. For when he turned to examine the animal’s body and to heave it over, he felt the warmth of a life within. It was a doe with a live fawn within waiting to be born. He hesitated. It was as if the whole of nature was listening and closing in on him as a presence. It was as if the wilderness was human and pleading with him, while the car’s purring engine, the car pointing ahead telling him to hurry on. Obviously at one level, the poem is a statement about the relation between the human, technology and the environment. But the poet reframes the statement in terms of a deeper insight - that nature is a presence that calls us into communion with it. There are shades of Mary Oliver here when she warns us: ‘Do you think the world in only an entertainment for you?’

The poet is realising that nature is more than an entertainment to be picked up and dropped when it suits us. Two low-key phrases convey the spiritual journey he is making: I stood, and I thought hard for us all. In the poem’s last lines a communion has formed between man (the poet and all of us), the doe, the live fawn within her and the wilderness itself. Even the alien car participates, offering the warmth of its exhaust with the colour red becoming an incipient friendly glow in the dark. The communion experience makes it easier for the poet to do what he reluctantly has to do. And we also get a sense that the wilderness itself forgives him because of the respect he has shown.

Messages to: Jo O'Donovan rsm

Poetry commentary by Sr Jo previously published on mercyworld.org:

* 'Men Go To God' by Dietrich Bonhoeffer

* 'Advent' by Patrick Kavanagh

* 'This Above All is Precious and Remarkable' by John Wain

* 'Spring and Fall: To a Young Child' by GM Hopkins sj

Image: William Stafford. Photographer Christopher Ritter. Licensed under fair use