September 24, 2018

Mercy Day

To My Daughter Betty, the Gift of God

In wiser days my darling rosebud blown

To beauty proud as was your mother’s prime.

In that desired, delayed, incredible time,

You’ll ask why I abandoned you, my own,

And the dear heart that was your baby throne,

To dice with death. And oh! They’ll give you rhyme

And reason: some will call the thing sublime,

And some decry it in a knowing tone.

So here, while the mad guns curse overhead,

And tired men sigh with mud for couch and floor,

Know that we fools, now with the foolish dead,

Died not for flag nor King, nor Emperor,

But for a dream, born in a herdman’s shed,

And for the secret Scripture of the poor.

- Tom Kettle (1880-1916)

As we know, 2016 has been a special year in Ireland for commemoration of events leading up to and following on the Easter Rising of 1916 and the founding of the Irish Free state. For this reason I drew your attention to Joseph Mary Plunkett, one of the 1916 leaders of the Rising, who, with the other leaders, was executed in the aftermath of the Rising. Like a number of those involved he was a poet, and I included I See His Blood Upon the Rose. But there is another poet of this period who must be reclaimed because of his haunting poem. This remarkable man was in British uniform however, and was leading the 9th Battalion of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers through no-man’s-land near Ginchy in the Somme region of France when he was killed.

Tom Kettle was a man of many parts, a convinced nationalist, a one-time MP in Westminster, a barrister, a university professor of economics, a writer and poet – in every sense a public intellectual. He was a co-founder of the Volunteers, 1913, and in 1914 was sent by them to Belgium on an arms purchasing mission, where he witnessed the outbreak of the Great War. Horrified by the atrocities committed against the helpless population of a small country and seeing the same in France, he decried the invasion tactics of Prussian militarism as a war of barbarism against civilization. On his return to Dublin, not aware of the imminence of the Easter Rising, and hoping that Britain would eventually keep to its promise of Home Rule for the country, he chose to participate in the Great War. With command of a division of the Dublin Fusiliers, he left Ireland like so many others ‘to dice with death’ on the battlefields of the Somme. This decision was not taken lightly. In this heart-felt poem written in the trenches two days before he died, he pleads with his wife and daughter not to blame him. We may ask: do the last lines of the poem imply that there was some greater love impelling him? We also know that in those days many of the young men from Dublin and other cities at that time were unemployed and extremely poor, and went to the war in need of ‘the Kings’s shilling’. But that was their reality.

Tom Kettle was a man of many parts, a convinced nationalist, a one-time MP in Westminster, a barrister, a university professor of economics, a writer and poet – in every sense a public intellectual. He was a co-founder of the Volunteers, 1913, and in 1914 was sent by them to Belgium on an arms purchasing mission, where he witnessed the outbreak of the Great War. Horrified by the atrocities committed against the helpless population of a small country and seeing the same in France, he decried the invasion tactics of Prussian militarism as a war of barbarism against civilization. On his return to Dublin, not aware of the imminence of the Easter Rising, and hoping that Britain would eventually keep to its promise of Home Rule for the country, he chose to participate in the Great War. With command of a division of the Dublin Fusiliers, he left Ireland like so many others ‘to dice with death’ on the battlefields of the Somme. This decision was not taken lightly. In this heart-felt poem written in the trenches two days before he died, he pleads with his wife and daughter not to blame him. We may ask: do the last lines of the poem imply that there was some greater love impelling him? We also know that in those days many of the young men from Dublin and other cities at that time were unemployed and extremely poor, and went to the war in need of ‘the Kings’s shilling’. But that was their reality.

Commentators on Kettle have said that he was a man of culture, European as well as Irish. He believed it was only through being European and looking outward that Ireland could achieve its true potential as a nation. But he was also astute enough to know that following the Easter Rising that he and the many like him would find themselves on ‘the wrong side of history’ and be forgotten. But thankfully at last, that has been righted.

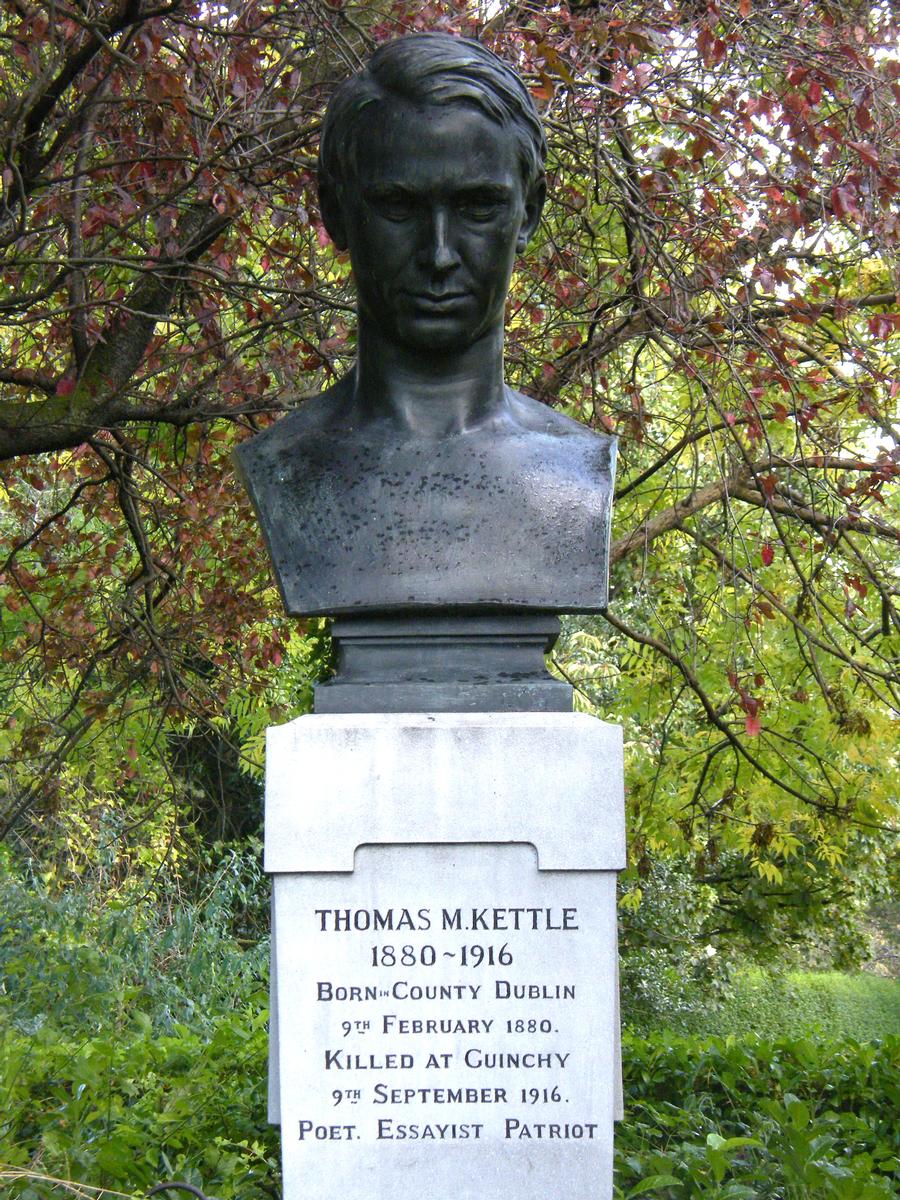

This year the official remembrance of British war dead was marked in the British Isles on Remembrance Sunday, November 13th, 2016. On that date also a number of remembrance events occurred throughout Ireland for relatives who died in the Great War. The official Government Remembrance was honoured by a French presence. A gift was made to Ireland of a W.W.I memorial and unveiled at Glasnevin cemetery. The memorial is a replica of a wooden cross built by men of the 16th Irish Division for Ginchy churchyard in Northern France, 1916. It was near Ginchy that Tom Kettle died. It remains unclear what happened to his body, but there is a memorial bust to him in St Stephen’s Green, Dublin. The plinth also carries the final lines of his most famous poem. I believe that in times of confusion, it is only the poets who can save us. These lines are a sufficient epitaph for Kettle himself and for the 50,000 from the island of Ireland, who died in the Great War.

Messages to: Jo O'Donovan rsm

Poetry commentary by Sr Jo previously published on mercyworld.org:

* The Hospital by Patrick Kavanagh

* I See His blood Upon the Rose by Joseph Plunkett

* Eucharist by Nora Wall rsm

* 'Spring' by Gerard Manley Hopkins sj

*'Travelling through the Dark' by William Stafford

* 'Men Go To God' by Dietrich Bonhoeffer

* 'Advent' by Patrick Kavanagh

* 'This Above All is Precious and Remarkable' by John Wain

* 'Spring and Fall: To a Young Child' by Gerard Manley Hopkins sj

Image: By Pilgab - Own work (own picture), CC BY-SA 3.0 Memorial in St Stephen's Green, Dublin