“Thus we go on” - Ending Sex Trafficking, Realising Catherine’s Vision in Our World Today

July 28, 2015

Sex trafficking is a growing problem in Ireland and around the world.

The work of the Mercy community to end this dreadful trade in human beings is rooted in Catherine’s mission to protect vulnerable women and children from exploitation. Catherine’s sense of the injustices faced by women and girls is as pertinent to the Mercy mission today as it was when she first opened her house on Baggot Street.

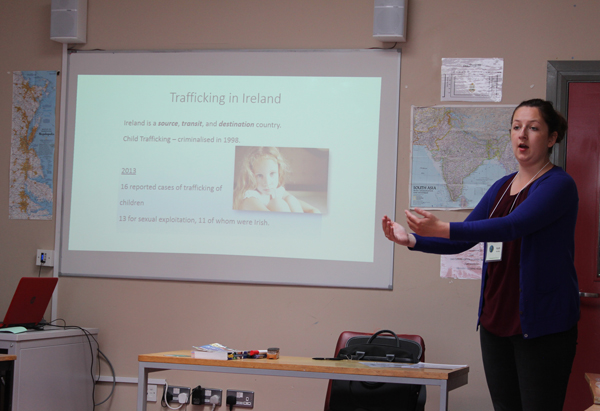

During the Young Mercy Leaders Pilgrimage, I was asked to give a workshop on the issue of sex trafficking and took the opportunity to explore some of the complex causes that drive this modern slavery. The reality is that the commercial sex trade is rooted in the systemic gender inequality which, despite great progress since Catherine’s day, women and girls must still endure.

We live in a society in which we are constantly bombarded by hyper-sexualised imagery of women and girls. Female sexuality permeates advertising, popular music, film, TV – even our female politicians are subjected to scrutiny of their physical appearance in a way male politicians are not. The commercialisation of women’s bodies is in evidence all around us. There is a clear link between this relentless commodification of female sexuality and the demand for commercial sex. The Mercy sisters working to end sex trafficking in Ireland support the Turn Off the Red Light campaign, which seeks to end the demand for prostitution by criminalising the buyer of sex – most often men - while decriminalising those selling sex – most often women and girls. This approach marks a radical shift in the way we think about and deal with the sex trade because it recognises prostitution as a symptom of gender inequality.

We will not bring an end to sex trafficking until we change attitudes and tackle the normalisation of objectifying women; we have to target demand in order to meaningfully impact the supply. The sexual objectification of women is a problem that affects all women in society, particularly young women like the Young Mercy Leaders. We don’t all have to be gung-ho human rights activists chaining ourselves to government buildings to challenge sex trafficking; we can challenge it in our daily lives by not tolerating the objectification of women, by speaking up when someone makes a “rape joke”, by challenging the casual, everyday sexism that women and girls are all too familiar with.

We often view victims of sex trafficking as somehow “other” to us; they are suffering in a tragedy too bleak to even imagine. And yet, when we accept that prostitution - the context in which sex trafficking occurs - is essentially a result of gender inequality, we see that we are all connected through this overarching injustice. We are compelled to act in solidarity with all those who suffer from the impact of systemic gender inequality. Unlike the majority of her peers, Catherine did not see the vulnerable women and children of Dublin as essentially different, or unworthy of concern, or “other”; she saw their struggle as her struggle, and so it is today. That is the challenge for all of us who want to be leaders in mercy.

- Ruth Kilcullen, Ireland